Hunter S. Thompson

Hunter S. Thompson | |

|---|---|

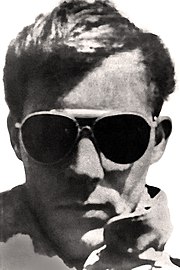

Thompson in 1971 | |

| Born | Hunter Stockton Thompson July 18, 1937 Louisville, Kentucky, U.S. |

| Died | February 20, 2005 (aged 67) Woody Creek, Colorado, U.S. |

| Pen name | Raoul Duke |

| Nickname | HST[1] |

| Genre | Gonzo journalism |

| Literary movement | New Journalism |

| Years active | 1958–2005 |

| Notable works |

|

| Spouse |

|

| Children | 1 |

| Signature | |

| |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch | |

| Service years | 1955–58 |

| Rank | |

| Service number | AF 15546879 |

| Unit | Strategic Air Command, Office of Information Services |

Hunter Stockton Thompson (July 18, 1937 – February 20, 2005) was an American journalist and author. He rose to prominence with the publication of Hell's Angels (1967), a book for which he spent a year living with the Hells Angels motorcycle club to write a first-hand account of their lives and experiences. In 1970, he wrote an unconventional article titled "The Kentucky Derby Is Decadent and Depraved" for Scanlan's Monthly, which further raised his profile as a countercultural figure. It also set him on the path to establishing his own subgenre of New Journalism that he called "Gonzo", a journalistic style in which the writer becomes a central figure and participant in the events of the narrative.

Thompson remains best known for Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas (1972), a book first serialized in Rolling Stone in which he grapples with the implications of what he considered the failure of the 1960s counterculture movement. It was adapted for film twice: loosely in 1980 in Where the Buffalo Roam and explicitly in 1998 in Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas.

Thompson ran unsuccessfully for sheriff of Pitkin County, Colorado in 1970 on the Freak Power ticket. He became known for his intense dislike of Richard Nixon, who he claimed represented "that dark, venal, and incurably violent side of the American character".[2] He covered George McGovern's 1972 presidential campaign for Rolling Stone and later collected the stories in book form as Fear and Loathing: On the Campaign Trail '72 (1973).

Starting in the mid-1970s, Thompson's output declined, as he struggled with the consequences of fame and substance abuse, and failed to complete several high-profile assignments for Rolling Stone. For much of the late 1980s and early 1990s, he worked as a columnist for the San Francisco Examiner. Most of his work from 1979 to 1994 was collected in The Gonzo Papers. He continued to write sporadically for various outlets, including Rolling Stone, Playboy, Esquire, and ESPN.com until the end of his life.

Thompson was known for his lifelong use of alcohol and illegal drugs, his love of firearms, and his iconoclastic contempt for authority. He often remarked: "I hate to advocate drugs, alcohol, violence, or insanity to anyone, but they've always worked for me."[3] Thompson died by suicide at the age of 67, following a series of health problems. Hari Kunzru wrote, "The true voice of Thompson is revealed to be that of American moralist ... one who often makes himself ugly to expose the ugliness he sees around him."[4]

Early life

[edit]Thompson was born into a middle-class family in Louisville, Kentucky, the first of three sons of Virginia Davison Ray (1908, Springfield, Kentucky – March 20, 1998, Louisville), who worked as head librarian at the Louisville Free Public Library and Jack Robert Thompson (September 4, 1893, Horse Cave, Kentucky – July 3, 1952, Louisville), a public insurance adjuster and World War I veteran.[5] His parents were introduced by a friend from Jack's fraternity at the University of Kentucky in September 1934, and married on November 2, 1935.[6] Journalist Nicholas Lezard of The Guardian stated that Thompson's first name, Hunter, came from an ancestor on his mother's side, the Scottish surgeon John Hunter.[7] A more direct attribution is that Thompson's first and middle name, Hunter Stockton, came from his maternal grandparents, Prestly Stockton Ray and Lucille Hunter.[8]

In December 1943, when Thompson was six years old, the family settled in the affluent Cherokee Triangle neighborhood of The Highlands.[9] On July 3, 1952, when Thompson was 14, his father died of myasthenia gravis at age 58. Hunter and his brothers were raised by their mother. Virginia worked as a librarian to support her children and was described as a "heavy drinker" following her husband's death.[6][10]

Education

[edit]

Interested in sports and athletically inclined from a young age, Thompson co-founded the Hawks Athletic Club while attending I.N. Bloom Elementary School,[11] which led to an invitation to join Louisville's Castlewood Athletic Club[11] for adolescents that prepared them for high-school sports. Ultimately, he never joined a sports team in high school.[6] He grew up in the same neighborhood as mystery novelist Sue Grafton, who was a few years behind him in school.[12]

Thompson attended I.N. Bloom Elementary School,[13] Highland Middle School, and Atherton High School, before transferring to Louisville Male High School in fall 1952.[14] Also in 1952, he was accepted as a member of the Athenaeum Literary Association, a school-sponsored literary and social club that dated to 1862. Its members at the time came from Louisville's upper-class families, and included Porter Bibb, who later became the first publisher of Rolling Stone at Thompson's behest. During this time, Thompson read and admired J. P. Donleavy's The Ginger Man.[15]

As an Athenaeum member, Thompson contributed articles to and helped produce the club's yearbook The Spectator until the group ejected Thompson in 1955 for criminal activity.[6] Charged as an accessory to robbery after being in a car with the perpetrator, Thompson was sentenced to 60 days in Kentucky's Jefferson County Jail. He served 31 days and, during his incarceration, was refused permission to take final exams, preventing his graduation.[15] He enlisted in the United States Air Force upon release.[6]

Military service

[edit]

Thompson completed basic training at Lackland Air Force Base in San Antonio, Texas and transferred to Scott Air Force Base in Belleville, Illinois to study electronics. He applied to become an aviator, but the Air Force's aviation-cadet program rejected his application. In 1956, he transferred to Eglin Air Force Base near Fort Walton Beach, Florida. While serving at Eglin, he took evening classes at Florida State University.[16] At Eglin, he landed his first professional writing job as sports editor of The Command Courier by lying about his job experience. As sports editor, Thompson traveled around the United States with the Eglin Eagles football team, covering its games. In early 1957, he wrote a sports column for The Playground News, a local newspaper in Fort Walton Beach, Florida. His name did not appear on the column because Air Force regulations forbade outside employment.[6]

In 1958, while he was an airman first class, his commanding officer recommended him for an early honorable discharge. "In summary, this airman, although talented, will not be guided by policy," chief of information services Colonel William S. Evans wrote to the Eglin personnel office. "Sometimes his rebel and superior attitude seems to rub off on other airmen staff members."[17]

Early journalism career

[edit]After leaving the Air Force, Thompson worked as sports editor for a newspaper in Jersey Shore, Pennsylvania,[18] before relocating to New York City. There he audited several courses at the Columbia University School of General Studies.[19] During this time he worked briefly for Time as a copy boy for $51 a week. At work, he typed out parts of F. Scott Fitzgerald's The Great Gatsby and Ernest Hemingway's A Farewell to Arms in order to learn the authors' rhythms and writing styles.[20] In 1959, Time fired him for insubordination.[21] Later that year, he worked as a reporter for The Middletown Daily Record in Middletown, New York. He was fired from this job after damaging an office candy machine and arguing with the owner of a local restaurant who happened to be an advertiser with the paper.[21]

In 1960, Thompson moved to San Juan, Puerto Rico, to take a job with the sporting magazine El Sportivo, which ceased operations soon after his arrival. Thompson applied for a job with the Puerto Rican English-language daily The San Juan Star, but its managing editor, future novelist William J. Kennedy, turned him down. Nonetheless, the two became friends. After the demise of El Sportivo, Thompson worked as a stringer for the New York Herald Tribune and a few other stateside papers on Caribbean issues, with Kennedy working as his editor.[22][23]

After returning to mainland United States in 1961, Thompson visited San Francisco and eventually lived in Big Sur, where he spent eight months as security guard and caretaker at Slates Hot Springs, just before it became the Esalen Institute. At the time, Big Sur was a Beat outpost and home of Henry Miller and the screenwriter Dennis Murphy, both of whom Thompson admired. During this period, he published his first magazine feature in Rogue about the artisan and bohemian culture of Big Sur and worked on The Rum Diary. He managed to publish one short story, "Burial at Sea," which also appeared in Rogue. It was his first piece of published fiction.[24] The Rum Diary, based on Thompson's experiences in Puerto Rico, was finally published in 1998 and in 2011 was adapted as a motion picture. Paul Perry notes that Thompson exhibited extreme homophobia while at Big Sur, making violent threats to expel gay bathers from local hot springs.[25]

In May 1962, Thompson traveled to South America for a year as a correspondent for the Dow Jones-owned weekly paper, the National Observer.[26] In Brazil, he spent several months as a reporter for the Rio de Janeiro-based Brazil Herald, the country's only English-language daily. His longtime girlfriend Sandra Dawn Conklin (subsequently Sondi Wright) joined him in Rio. They married on May 19, 1963, shortly after returning to the United States, and lived briefly in Aspen, Colorado. Sandy was eight months pregnant when they relocated to Glen Ellen, California. Their son, Juan Fitzgerald Thompson, was born in March 1964.[27][8] During the summer of that same year, Hunter began taking Dexedrine, which is what he would predominantly use for writing up until around 1974 when he began to write mostly under the influence of cocaine.[28]

Thompson continued to write for the National Observer on an array of domestic subjects during the early 60s. One story told of his 1964 visit to Ketchum, Idaho, to investigate the reasons for Ernest Hemingway's suicide.[29] While there, he stole a pair of elk antlers hanging above the front door of Hemingway's cabin. Later that year, Thompson moved to San Francisco, where he attended the 1964 GOP Convention at the Cow Palace. Thompson severed his ties with the Observer after his editor refused to print his review of Tom Wolfe's 1965 essay-collection The Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby.[30] He later immersed himself in the drug and hippie culture taking root in the area, and soon began writing for the Berkeley underground paper Spider.[31]

Hell's Angels

[edit]In 1965, Carey McWilliams, editor of The Nation, hired Thompson to write a story about the Hells Angels motorcycle club in California. At the time, Thompson was living in a house near San Francisco's Haight-Ashbury neighborhood, where the Hells Angels lived across from the Grateful Dead.[32] His article appeared on May 17, 1965, after which he received several book offers and spent the next year living and riding with the club. The relationship broke down when the bikers perceived that Thompson was exploiting them for personal gain and demanded a share of his profits. An argument at a party resulted in Thompson suffering a savage beating (or "stomping", as the Angels referred to it) when Thompson intervened to protect a dog and a woman from physical abuse by a punk.[33][34] Random House published the hard cover Hell's Angels: The Strange and Terrible Saga of the Outlaw Motorcycle Gangs in 1966, and the fight between Thompson and the Angels was well-marketed. CBC Television even broadcast an encounter between Thompson and Hells Angel Skip Workman before a live studio audience.[35]

A New York Times review praised the work as an "angry, knowledgeable, fascinating, and excitedly written book", that shows the Hells Angels "not so much as dropouts from society but as total misfits, or unfits—emotionally, intellectually and educationally unfit to achieve the rewards, such as they are, that the contemporary social order offers". The reviewer also praised Thompson as a "spirited, witty, observant, and original writer; his prose crackles like motorcycle exhaust".[36]

Thompson also aided Danny Lyon in his role as photographer with the Outlaws Motorcycle Club, telling Lyon that he should not join the club unless "it was absolutely necessary for photo action".

Late 1960s

[edit]Following the success of Hell's Angels, Thompson sold stories to several national magazines, including The New York Times Magazine, Esquire, Pageant, and Harper's.[37]

In 1967, shortly before the Summer of Love, Thompson wrote "The 'Hashbury' is the Capital of the Hippies" for The New York Times Magazine. He criticized San Francisco's hippies as devoid of both the political convictions of the New Left and the artistic core of the Beats, resulting in a culture overrun with young people who spent their time in the pursuit of drugs. "The thrust is no longer for 'change' or 'progress' or 'revolution', but merely to escape, to live on the far perimeter of a world that might have been – perhaps should have been – and strike a bargain for survival on purely personal terms," he wrote.[38]

Later that year, Thompson and his family moved back to Colorado and rented a house in Woody Creek, a small mountain hamlet outside Aspen. In early 1969, Thompson received a $15,000 royalty check for the paperback sales of Hell's Angels and used a portion of the proceeds on a down payment on a home and property where he would live for the rest of his life.[39] It was a 110-acre piece of land that cost him $75,000.[40] He named the house Owl Farm and often described it as his "fortified compound".

In early 1968, Thompson signed the "Writers and Editors War Tax Protest" pledge, vowing to refuse tax payments in protest against the Vietnam War.[41] According to Thompson's letters from the period, he planned to write a book called The Joint Chiefs about "the death of the American Dream." He used a $6,000 advance from Random House to travel the country covering the 1968 United States presidential election and attend the Democratic National Convention in Chicago for research. He watched the clashes between police and anti-war protesters from his hotel, and later claimed that events had a significant effect on his political views, saying "I went to the Democratic convention as a journalist and returned a raving beast."[42] While Thompson never completed the book, he carried its theme into later work. He also signed a deal with Ballantine Books in 1968 to write a satirical book called The Johnson File about President Lyndon B. Johnson. A few weeks later, the deal fell through after Johnson withdrew from the election.[43]

Thompson was impressed by Rolling Stone magazine's coverage of the disastrous Altamont Free Concert in December 1969. After writing to Rolling Stone's editor, Jann Wenner, Thompson accepted an invitation to submit his work to the magazine, which soon became his primary outlet.[44]

Middle years

[edit]Aspen sheriff campaign

[edit]

| |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

In 1970, Thompson ran for sheriff of Pitkin County, Colorado, as part of a group of citizens running for local offices on the "Freak Power" ticket. The platform included promoting the decriminalization of drugs (for personal use only, not trafficking, as he disapproved of profiteering), tearing up the streets and turning them into grassy pedestrian malls, banning any building so tall as to obscure the view of the mountains, disarming all police forces, and renaming Aspen "Fat City" to deter investors. Thompson, having shaved his head, referred to the crew cut-wearing Republican candidate as "my long-haired opponent".[45]

With polls showing him with a slight lead in a three-way race, Thompson appeared at Rolling Stone magazine headquarters in San Francisco with a six-pack of beer in hand, and declared to editor Jann Wenner that he was about to be elected sheriff of Aspen, Colorado, and wished to write about the "Freak Power" movement.[46] "The Battle of Aspen" was Thompson's first feature for the magazine carrying the byline "By: Dr. Hunter S. Thompson (Candidate for Sheriff)". (Thompson's "Dr" certification was obtained from a mail-order church while he was in San Francisco in the sixties.) Despite the publicity, Thompson lost the election. While carrying the city of Aspen, he garnered only 44% of the county-wide vote in what had become, after the withdrawal of the Republican candidate, a two-way race. Thompson later said that the Rolling Stone article mobilized more opposition to the Freak Power ticket than supporters.[47] The episode was the subject of the 2020 documentary film Freak Power: The Ballot or the Bomb. Writing of the episode more than fifty years later, Wenner wrote "Aspen didn't get a new sheriff, but I realized that, in Hunter, I had a fellow traveller."[48]

Birth of Gonzo

[edit]Also in 1970, Thompson wrote an article entitled "The Kentucky Derby Is Decadent and Depraved" for the short-lived new journalism magazine Scanlan's Monthly. For that article, editor Warren Hinckle paired Thompson with illustrator Ralph Steadman, who drew expressionist illustrations with lipstick and eyeliner. Thompson's story virtually ignored the race and focused instead on the drunken revelry surrounding the annual event in his hometown. Writing in the first person, he sets the debauchery against the backdrop of the American political scene of the moment: President Richard Nixon had ordered bombing of Cambodia and four students had been killed by Ohio National Guard troops at Kent State University, in a massacre which occurred only two days later.

Thompson and Steadman collaborated regularly after that. Although it was not widely read, the article was the first to use the techniques of Gonzo journalism, a style Thompson later employed in almost every literary endeavor. The manic first-person subjectivity of the story was reportedly the result of sheer desperation; he was facing a looming deadline and started sending the magazine pages ripped out of his notebook.

The first use of the word "Gonzo" to describe Thompson's work is credited to the journalist Bill Cardoso, who first met Thompson on a bus full of journalists covering the 1968 New Hampshire primary. In 1970, Cardoso (who was then the editor of The Boston Globe Sunday Magazine) wrote to Thompson praising the "Kentucky Derby" piece as a breakthrough: "This is it, this is pure Gonzo. If this is a start, keep rolling." According to Steadman, Thompson took to the word right away and said, "Okay, that's what I do. Gonzo."[49] Thompson's first published use of the word appears in Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas: "Free Enterprise. The American Dream. Horatio Alger gone mad on drugs in Las Vegas. Do it now: pure Gonzo journalism."

Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas

[edit]

The book for which Thompson gained most of his fame began during the research for "Strange Rumblings in Aztlan," an exposé for Rolling Stone on the 1970 killing of the Mexican American television journalist Rubén Salazar. Salazar had been shot in the head at close range with a tear-gas canister fired by officers of the Los Angeles County Sheriff's Department during the National Chicano Moratorium March against the Vietnam War. One of Thompson's sources for the story was Oscar Zeta Acosta, a prominent Mexican American activist and attorney. Finding it difficult to talk in the racially tense atmosphere of Los Angeles, Thompson and Acosta decided to travel to Las Vegas, and take advantage of an assignment by Sports Illustrated to write a 250-word photograph caption on the Mint 400 motorcycle race held there.

What was to be a short caption quickly grew into something else entirely. Thompson first submitted to Sports Illustrated a manuscript of 2,500 words, which was, as he later wrote, "aggressively rejected." Rolling Stone publisher Jann Wenner liked "the first 20 or so jangled pages enough to take it seriously on its own terms and tentatively scheduled it for publication — which gave me the push I needed to keep working on it", Thompson wrote.[50] Wenner, describing his first impression of it years later, called it "Sharp and insane."[48]

To develop the story, Thompson and Acosta returned to Las Vegas to attend a drug enforcement conference. The two trips became the basis for "Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas," which Rolling Stone serialized in two parts in November 1971. Random House published a book version the following year. It is written as a first-person account by a journalist named Raoul Duke with Dr. Gonzo, his "300-pound Samoan attorney." During the trip, Duke and his companion (always referred to as "my attorney") become sidetracked by a search for the American Dream, with "two bags of grass, 75 pellets of mescaline, five sheets of high-powered blotter acid, a salt shaker half full of cocaine, and a whole galaxy of multicolored uppers, downers, screamers, laughers ... and also a quart of tequila, a quart of rum, a case of Budweiser, a pint of raw ether, and two dozen amyls."

Coming to terms with the failure of the 1960s countercultural movement is a major theme of the novel, and the book was greeted with considerable critical acclaim. The New York Times praised it as "the best book yet written on the decade of dope".[51] "The Vegas Book", as Thompson referred to it, was a mainstream success and introduced his Gonzo journalism techniques to a wide public.

Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail '72

[edit]

In 1971 Wenner agreed to assign Thompson to cover the 1972 United States presidential election for Rolling Stone. Thompson was paid a retainer of $1,000 per month (equivalent to $7,523 in 2023) and rented a house near Rock Creek Park in Washington D.C. at the magazine's expense. He was also given a deal to publish a book on the campaign after its conclusion, which subsequently appeared as Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail '72 in early 1973. Insider books on presidential politics had become popular during the prior decade starting with Theodore H. White's Making of the President series, the first of which appeared in 1961, with additional volumes in 1965 and 1969. Their success raised the overall profile of journalists assigned to cover the quadrennial presidential election in the U.S., and it became a common phrase among them to say they were "...Doing a Teddy White," meaning they planned to write their own insider book on the campaign.[8]

Wenner had decided that Rolling Stone would cover the presidential election in part because of the passage in 1971 of the 26th Amendment to the Constitution of the United States which lowered the legal voting age from 21 to 18, making a large part of its mostly young readership suddenly eligible to vote. "We intended to politicize our generation and wrest this stirring force away from the fake politics of the revolutionary," Wenner wrote in his memoirs of the plan to collaborate with Thompson.[48]

Thompson's first campaign piece for Rolling Stone appeared as Fear and Loathing in Washington: Is This Trip Really Necessary? in the January 6, 1972, issue. The 14th and final installment appeared in the November 9 issue under the headline Ask Not For Whom The Bell Tolls....[52]

Throughout the year, Thompson traveled with candidates running in the 1972 Democratic Party presidential primaries for the right to challenge the incumbent president, Republican Richard Nixon in the general election. Thompson's coverage focused mainly on Sen. George McGovern of South Dakota, Sen. Edmund Muskie of Maine, the early leader, and former vice-president Hubert Humphrey. Thompson supported McGovern and wrote critical coverage of the rival campaigns.

In the April 13 installment entitled Fear and Loathing: The Banshee Screams in Florida, Thompson relates how someone having apparently lifted his press credential, terrorized Muskie and his staff on a campaign train. The incident was later revealed to be an elaborate prank. In another installment, Thompson relates rumors — rumors he later admitted he had originated — that Muskie had become addicted to the psychoactive drug Ibogaine. The story damaged Muskie's reputation and played a role in his loss of the nomination to McGovern. In another, he tracked down McGovern in a restroom in order to get a reaction quote after a senator from Iowa had switched his endorsement from McGovern to Muskie.

The series, and later, the book were both praised for breaking boundaries with a new approach to political journalism. The literary critic Morris Dickstein, wrote that Thompson had learned to "approximate the effect of mind-blasting drugs in his prose style," and that he "recorded the nuts and bolts of a presidential campaign with all the contempt and incredulity that other reporters must feel but censor out."[53]

Frank Mankiewicz, McGovern's campaign director, often described it as the "most accurate and least factual" account of the 1972 campaign. In one vivid, yet invented anecdote, Thompson describes how Mankiewicz had leapt out from behind a bush to attack him with a hammer. To an uninitiated reader, it might have been unclear at first if the action Thompson described was fanciful or factual, and that seemed to be part of the point. As biographer William McKeen wrote "He wrote for his own amusement, and if others came along for the ride, that was all right."[8]

Fame and its consequences

[edit]Thompson's journalistic work began to seriously suffer after his trip to Africa to cover the Rumble in the Jungle—the world heavyweight boxing match between George Foreman and Muhammad Ali—in 1974. He missed the match while intoxicated at his hotel and did not submit a story to the magazine. As Wenner put it to the film critic Roger Ebert in the 2008 documentary Gonzo: The Life and Work of Dr. Hunter S. Thompson, "After Africa, he just couldn't write. He couldn't piece it together".[54] It was in 1973 that Thompson tried cocaine for the first time and various friends, family members, and editors remarked that its impact upon his productivity and creativity was devastating.[55]

In 1975, Wenner assigned Thompson to travel to Vietnam to cover what appeared to be the end of the Vietnam War. Thompson arrived in Saigon just as South Vietnam was collapsing and as other journalists were leaving the country. Wenner allegedly canceled Thompson's medical insurance, which strained Thompson's relationship with Rolling Stone.[56] He soon fled the country and refused to file his report until the ten-year anniversary of the Fall of Saigon.[56] Wenner, writing in 2022, denied the claims that he cancelled Thompson's insurance, saying that Thompson spent most of his time in Saigon obsessing over evacuation plans. Thompson filed an unfinished dispatch that Wenner described "strong and promising, but nothing substantial." He then took a commercial flight to Bangkok where he met his wife for what Wenner described as a few weeks of "totally undeserved rest and recreation." While in Thailand, Thompson had a custom brass door plaque made that read "Rolling Stone: Global Affairs Suite. Dr. Hunter S. Thompson" marked with a map of the world and two lightning bolts. "That was it," Wenner wrote. "No story. Just that plaque."[48] Thompson later finished the story in time for the 10-year anniversary of the Fall of Saigon.[56]

Plans for Thompson to cover the 1976 presidential campaign for Rolling Stone and later publish a book fell through as Wenner dissolved Straight Arrow Press' book publishing division. Thompson claimed Wenner canceled the project without informing him.[46] In his memoirs, Wenner told a different story: "The issue wasn't money ... The real issue was whether he had the discipline to spend so much time on the campaign trail and whether he had that much to say about the same subject again." Thompson went on to spend a day with Jimmy Carter at the Georgia Governor's Mansion and write a 10,000-word cover story endorsing Carter for president. "After that, we were virtually an official part of the Carter campaign, and they treated us as such," Wenner wrote of the episode.[48]

From the late 1970s on, most of Thompson's literary output appeared as a four-volume series of books entitled The Gonzo Papers. Beginning with The Great Shark Hunt in 1979 and ending with Better Than Sex in 1994, the series is largely a collection of rare newspaper and magazine pieces from the pre-Gonzo period, along with almost all of his Rolling Stone pieces.

Starting around 1980, Thompson became less active by his standards. Aside from paid appearances, he largely retreated to his compound in Woody Creek, rejecting projects and assignments or failing to complete them. Despite a lack of new material, Wenner kept Thompson on the Rolling Stone masthead as chief of the "National Affairs Desk", a position he held until his death.

In 1980, Thompson divorced his wife, Sandra Conklin. The same year marked the release of Where the Buffalo Roam, a loose film adaptation based on Thompson's early 1970s work, starring Bill Murray as the writer. Murray eventually became one of Thompson's trusted friends. Later that year, Thompson relocated to Hawaii to research and write The Curse of Lono, a Gonzo-style account of the 1980 Honolulu Marathon. Extensively illustrated by Ralph Steadman, an iteration of the work first appeared in Running in 1981 as "The Charge of the Weird Brigade" and was later excerpted in Playboy in 1983.[57] The book was a disappointment, with its editor calling it "disorganized and incoherent."[58] It was poorly reviewed, and sales were disappointing.[59]

In 1983, he covered the U.S. invasion of Grenada but did not write or discuss the experiences until the publication of Kingdom of Fear in 2003. Also in 1983, at the behest of Terry McDonell, he wrote "A Dog Took My Place[60]", an exposé for Rolling Stone of the scandalous Roxanne Pulitzer divorce case and what he called the "Palm Beach lifestyle". The story included dubious insinuations of bestiality. Wenner described it as one of Thompson's "least-known but best pieces."[48] In 1985, Thompson accepted an advance to write about "feminist pornography" for Playboy.[61] As part of his research, he spent evenings at the Mitchell Brothers O'Farrell Theatre striptease club in San Francisco. The experience evolved into an as-yet-unpublished novel tentatively entitled The Night Manager.

Thompson next accepted a role as weekly media columnist and critic for The San Francisco Examiner. The position was arranged by former editor and fellow Examiner columnist Warren Hinckle.[62] As his editor at The Examiner, David McCumber described, "One week it would be acid-soaked gibberish with a charm of its own. The next week it would be incisive political analysis of the highest order."[63]

Many of these columns were collected in Gonzo Papers, Vol. 2: Generation of Swine: Tales of Shame and Degradation in the '80s (1988) and Gonzo Papers, Vol. 3: Songs of the Doomed: More Notes on the Death of the American Dream (1990), a collection of autobiographical reminiscences, articles, and previously unpublished material.

Later years

[edit]Thompson faced a sexual assault charge in March 1990 when former pornographic film director Gail Palmer claimed that after she denied his sexual advances while at his home, Thompson threw a drink at her and twisted her left breast.[64] He was tried for five felonies and three misdemeanors owing to the assault charge and allegations of drug abuse after the police raided his home. The charges were dropped two months later.[65]

Throughout the early 1990s, Thompson claimed to be at work on a novel entitled Polo Is My Life. It was briefly excerpted in Rolling Stone in 1994. Wenner described it as "Hunter's last big piece of feature writing," and described Thompson as abusive toward two editorial assistants assigned to him.[48] Thompson himself described it in 1996 as "a sex book—you know, sex, drugs, and rock and roll. It's about the manager of a sex theater who's forced to leave and flee to the mountains. He falls in love and gets in even more trouble than he was in the sex theater in San Francisco."[66] The novel was slated to be released by Random House in 1999, and was even assigned ISBN 0-679-40694-8, but was never published.

Thompson continued to publish irregularly in Rolling Stone, ultimately contributing 17 pieces to the magazine between 1984 and 2004.[67] "Fear and Loathing in Elko," published in 1992, was a well-received fictional rallying cry against the nomination of Clarence Thomas to a seat on the Supreme Court of the United States. "Trapped in Mr. Bill's Neighborhood" was a largely factual account of an interview with Bill Clinton at a Little Rock, Arkansas, steakhouse. Rather than traveling the campaign trail as he had done in previous presidential elections, Thompson monitored the proceedings on cable television; Better Than Sex: Confessions of a Political Junkie, his account of the 1992 presidential campaign, is composed of reactive faxes to Rolling Stone. In 1994, the magazine published "He Was a Crook", a "scathing" obituary of Richard Nixon.[68]

In November 2004, Rolling Stone published Thompson's final magazine feature "The Fun-Hogs in the Passing Lane: Fear and Loathing, Campaign 2004", a brief account of the 2004 presidential election in which he compared the outcome of the Bush v. Gore court case to the Reichstag fire and formally endorsed Senator John Kerry, a longtime friend, for president.

Fear and Loathing redux

[edit]In 1996, Modern Library reissued Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas along with "Strange Rumblings in Aztlan," "The Kentucky Derby Is Decadent and Depraved," and "Jacket Copy for Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas." Two years later, the film Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas generated new interest in Thompson and his work, and a paperback edition was published as a tie-in. The same year, an early novel, The Rum Diary, was published. Two volumes of collected letters also appeared during this time.

Thompson's next, and penultimate, collection, Kingdom of Fear: Loathsome Secrets of a Star-Crossed Child in the Final Days of the American Century, was widely publicized as Thompson's first memoir. Published in 2003, it combined new material (including reminiscences of the O'Farrell Theater), selected newspaper and digital clippings, and other older works.

Thompson finished his journalism career in the same way it had begun: writing about sports. From 2000 until his death in 2005, he wrote a weekly column for ESPN.com's Page 2 entitled "Hey, Rube." In 2004, Simon & Schuster collected some of the columns from the first few years and released them in mid-2004 as Hey Rube: Blood Sport, the Bush Doctrine, and the Downward Spiral of Dumbness.

Thompson married assistant Anita Bejmuk on April 23, 2003.

Death

[edit]At 5:42 pm on February 20, 2005, Thompson died from a self-inflicted gunshot wound to the head at Owl Farm, his "fortified compound" in Woody Creek, Colorado. His son Juan, daughter-in-law Jennifer, and grandson were visiting for the weekend. His wife Anita, who was at the Aspen Club, was on the phone with him as he cocked the gun. According to the Aspen Daily News, Thompson asked her to come home to help him write his ESPN column, then set the receiver on the counter. Anita said she mistook the cocking of the gun for the sound of his typewriter keys and hung up as he fired. Will, his grandson, and Jennifer were in the next room when they heard the gunshot, but mistook the sound for a book falling and did not check on Thompson immediately. Juan Thompson found his father's body. According to the police report and Anita's cell phone records,[69] he called the sheriff's office half an hour later, then walked outside and fired three shotgun blasts into the air to "mark the passing of his father." The police report stated that in Thompson's typewriter was a piece of paper with the date "Feb. 22 '05" and a single word, "counselor."[70]

Years of alcohol and cocaine abuse contributed to his problem with depression. Thompson's inner circle told the press that he had been depressed and always found February a "gloomy" month, with football season over and the harsh Colorado winter weather. He was also upset over his advancing age and chronic medical problems, including a hip replacement; he would frequently mutter "This kid is getting old." Rolling Stone published what Douglas Brinkley described as a suicide note written by Thompson to his wife, titled "Football Season Is Over." It read:

No More Games. No More Bombs. No More Walking. No More Fun. No More Swimming. 67. That is 17 years past 50. 17 more than I needed or wanted. Boring. I am always bitchy. No Fun—for anybody. 67. You are getting Greedy. Act your old age. Relax — This won't hurt.[71]

Thompson's collaborator and friend Ralph Steadman wrote:

... He told me 25 years ago that he would feel real trapped if he didn't know that he could commit suicide at any moment. I don't know if that is brave or stupid or what, but it was inevitable. I think that the truth of what rings through all his writing is that he meant what he said. If that is entertainment to you, well, that's OK. If you think that it enlightened you, well, that's even better. If you wonder if he's gone to Heaven or Hell, rest assured he will check out them both, find out which one Richard Milhous Nixon went to—and go there. He could never stand being bored. But there must be Football too—and Peacocks ...[72]

Funeral

[edit]On August 20, 2005, in a private funeral at Owl Farm, Thompson's ashes were fired from a cannon. This was accompanied by red, white, blue, and green fireworks—all to the tune of Norman Greenbaum's "Spirit in the Sky" and Bob Dylan's "Mr. Tambourine Man".[73] The cannon was placed atop a 153-foot (47 m) tower which had the shape of a double-thumbed fist clutching a peyote button, a symbol originally used in his 1970 campaign for sheriff of Pitkin County, Colorado. The plans for the monument were initially drawn by Thompson and Steadman, and were shown as part of an Omnibus program on the BBC titled Fear and Loathing in Gonzovision (1978). It is included as a special feature on the second disc of the 2004 Criterion Collection DVD release of Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, and labeled as Fear and Loathing on the Road to Hollywood.

According to his widow, Anita, the $3 million funeral was funded by actor Johnny Depp, who was a close friend of Thompson's. Depp told the Associated Press, "All I'm doing is trying to make sure his last wish comes true. I just want to send my pal out the way he wants to go out."[73] An estimated 280 people attended, including Steadman; U.S. Senators John Kerry and George McGovern;[74] 60 Minutes correspondents Ed Bradley and Charlie Rose; actors Jack Nicholson, John Cusack, Bill Murray, Benicio del Toro, Sean Penn, and Josh Hartnett; and musicians Lyle Lovett, John Oates and David Amram.

Legacy

[edit]Writing style

[edit]Thompson is often credited as the creator of Gonzo journalism, a style of writing that blurs distinctions between fiction and nonfiction. His work and style are considered to be a major part of the New Journalism literary movement of the 1960s and 1970s, which attempted to break free from the purely objective style of mainstream reportage of the time. Thompson almost always wrote in the first person, while extensively using his own experiences and emotions to color "the story" he was trying to follow.

Despite him having personally described his work as "Gonzo", it fell to later observers to articulate what the term actually meant. While Thompson's approach clearly involved injecting himself as a participant in the events of the narrative, it also involved adding invented, metaphoric elements, thus creating, for the uninitiated reader, a seemingly confusing amalgam of facts and fiction notable for the deliberately blurred lines between one and the other. Thompson, in a 1974 interview in Playboy addressed the issue himself, saying, "Unlike Tom Wolfe or Gay Talese, I almost never try to reconstruct a story. They're both much better reporters than I am, but then, I don't think of myself as a reporter." Tom Wolfe would later describe Thompson's style as "... part journalism and part personal memoir admixed with powers of wild invention and wilder rhetoric."[75] Or as one description of the differences between Thompson and Wolfe's styles would elaborate, "While Tom Wolfe mastered the technique of being a fly on the wall, Thompson mastered the art of being a fly in the ointment."[76]

The majority of Thompson's most popular and acclaimed work appeared within the pages of Rolling Stone magazine. Publisher Jan Wenner said Thompson was "in the DNA of Rolling Stone".[48] Along with Joe Eszterhas and David Felton, Thompson was instrumental in expanding the focus of the magazine past music criticism; indeed, Thompson was the only staff writer of the epoch never to contribute a music feature to the magazine. Nevertheless, his articles were always peppered with a wide array of pop music references ranging from Howlin' Wolf to Lou Reed. Armed with early fax machines wherever he went, he became notorious for haphazardly sending sometimes illegible material to the magazine's San Francisco offices as an issue was about to go to press.

Wenner said Thompson tended to work "in long bursts of energy, awake until dawn or, too often, two dawns." He said keeping Thompson on track when finishing a piece required "...companionship, or what editors call hand-holding, but in Hunter's case it was more like being a junior officer in his war. He required his creature comforts, which meant the right kind of typewriter and a certain color paper, Wild Turkey, the right drugs, and the proper music."[48]

Robert Love, Thompson's editor of 23 years at Rolling Stone, wrote in the Columbia Journalism Review that "the dividing line between fact and fancy rarely blurred, and we didn't always use italics or some other typographical device to indicate the lurch into the fabulous. But if there were living, identifiable humans in a scene, we took certain steps ... Hunter was a close friend of many prominent Democrats, veterans of the ten or more presidential campaigns he covered, so when in doubt, we'd call the press secretary. 'People will believe almost any twisted kind of story about politicians or Washington,' he once said, and he was right."[77]

Discerning the line between the fact and fiction of Thompson's work presented a practical problem for editors and fact-checkers. Love called fact-checking Thompson's work "one of the sketchiest occupations ever created in the publishing world", and "for the first-timer ... a trip through a journalistic fun house, where you didn't know what was real and what wasn't. You knew you had better learn enough about the subject at hand to know when the riff began and reality ended. Hunter was a stickler for numbers, for details like gross weight and model numbers, for lyrics and caliber, and there was no faking it."[77]

Persona

[edit]Thompson often used a blend of fiction and fact when portraying himself in his writing, too, sometimes using the name Raoul Duke as an author surrogate whom he generally described as a callous, erratic, self-destructive journalist, constantly drinking and taking hallucinogenics. In the early 1980s, Wenner spoke with Thompson about his alcoholism and addiction to cocaine, and offered to pay for drug treatment. "Hunter was polite and firm;" Wenner wrote in 2022. "He had thought about it and didn't feel he could or would change. He felt that [his drug abuse] was a key to his talent. He said that if he didn't do drugs, he would have the mind of an accountant. The abuse was already taking a toll on his gifts.... It was just too late, and he knew it."[48]

In the late 1960s, Thompson acquired the title of "Doctor" from the Church of the New Truth.[78][79]

A number of critics have commented that as he grew older, the line that distinguished Thompson from his literary self became increasingly blurred.[80][81][82] Thompson admitted during a 1978 BBC interview that he sometimes felt pressured to live up to the fictional self that he had created, adding, "I'm never sure which one people expect me to be. Very often, they conflict—most often, as a matter of fact. ... I'm leading a normal life and right alongside me there is this myth, and it is growing and mushrooming and getting more and more warped. When I get invited to, say, speak at universities, I'm not sure if they are inviting Duke or Thompson. I'm not sure who to be."[83]

Thompson's writing style and eccentric persona gave him a cult following in both literary and drug circles, and his cult status expanded into broader areas after being portrayed three times in major motion pictures. Hence, both his writing style and persona have been widely imitated, and his likeness has even become a popular costume choice for Halloween.[84]

Political beliefs

[edit]Thompson was a firearms and explosives enthusiast (in his writing and in life) and owned a large collection of handguns, rifles, shotguns, and various automatic and semiautomatic weapons, along with numerous forms of gaseous crowd-control and many homemade devices.[citation needed] He was a proponent of the right to bear arms and privacy rights.[85] A member of the National Rifle Association of America,[86] Thompson was also co-creator of the Fourth Amendment Foundation, an organization to assist victims in defending themselves against unwarranted search and seizure.[87]

Part of his work with the Fourth Amendment Foundation centered around support of Lisl Auman, a Colorado woman who was sentenced for life in 1997 under felony murder charges for the death of police officer Bruce VanderJagt, despite contradictory statements and dubious evidence.[88] Thompson organized rallies, provided legal support, and co-wrote an article in the June 2004 issue of Vanity Fair outlining the case. The Colorado Supreme Court eventually overturned Auman's sentence in March 2005, shortly after Thompson's death, and Auman is now free. Auman's supporters claim Thompson's support and publicity resulted in the successful appeal.[89]

Thompson was also an ardent supporter of drug legalization and became known for his detailed accounts of his own drug use. He was an early supporter of the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws and served on the group's advisory board for over 30 years, until his death.[90] He told an interviewer in 1997 that drugs should be legalized "[a]cross the board. It might be a little rough on some people for a while, but I think it's the only way to deal with drugs. Look at Prohibition; all it did was make a lot of criminals rich."[66]

In a 1965 letter to his friend Paul Semonin, Thompson explained an affection for the Industrial Workers of the World, "I have in recent months come to have a certain feeling for Joe Hill and the Wobbly crowd who, if nothing else, had the right idea. But not the right mechanics. I believe the IWW was probably the last human concept in American politics."[91] In another letter to Semonin, Thompson wrote that he agreed with Karl Marx, and compared him to Thomas Jefferson.[92] In a letter to William Kennedy, Thompson confided that he was "coming to view the free enterprise system as the single greatest evil in the history of human savagery."[93] In the documentary Breakfast with Hunter, Thompson is seen in several scenes wearing different Che Guevara T-shirts. Additionally, actor and friend Benicio del Toro has stated that Thompson kept a "big" picture of Che in his kitchen.[94] Thompson wrote on behalf of African-American rights and the civil rights movement.[95] He strongly criticized the dominance in American society of what he called "white power structures".[96]

After the September 11 attacks, Thompson voiced skepticism regarding the official story on who was responsible for the attacks. He speculated to several interviewers that it had been conducted by the U.S. government or with the government's assistance, though readily admitting he had no way to prove his theory.[97]

In 2004, Thompson wrote: "[Richard] Nixon was a professional politician, and I despised everything he stood for—but if he were running for president this year against the evil Bush–Cheney gang, I would happily vote for him."[98]

Scholarships

[edit]Thompson's widow established two scholarship funds at Columbia University School of General Studies for U.S. military veterans and the University of Kentucky for journalism students.[99][19][100][101] Colorado NORML created the Hunter S. Thompson Scholarship to pay all expenses for a lawyer or law student to attend the NORML Legal Committee Conference in Aspen, generally the first few days of June each year. The funding from a silent auction has paid for two winners for some years. Many winners have gone on to become important cannabis lawyers on state and national levels.[102]

Works

[edit]Awards, accolades, and tributes

[edit]- Thompson was named a Kentucky Colonel by the governor of Kentucky in a December 1996 tribute ceremony where he also received keys to the city of Louisville.[103]

- Dale Gribble, a main character on Fox's animated sitcom King of the Hill, is based on Thompson in terms of appearance and lifestyle.[104]

- Uncle Duke of the comic strip Doonesbury began as a straightforward parody of Thompson's alter ego Raoul Duke. Though he has morphed over time into having his own history and traits, his core persona of being a drug- and gun- loving trickster is clearly rooted in Thompson's Duke. While the character initially annoyed Thompson a great deal, he later said that "it no longer bothers me." [105]

- Author Tom Wolfe has called Thompson the greatest American comic writer of the 20th century.[75]

- Asked in an interview with Jody Denberg on KGSR Studio, in 2000, whether he would ever consider writing a book "like [his] buddy Hunter S. Thompson", the musician Warren Zevon responded: "Let's remember that Hunter S. Thompson is the finest writer of our generation; he didn't just toss off a book the other day..."[106]

- Thompson appeared on the cover of the 1,000th issue of Rolling Stone, May 18 – June 1, 2006, as a devil playing the guitar next to the two "L"'s in the word "Rolling". Johnny Depp also appeared on the cover.[107]

- Many have suggested that General Hunter Gathers in the Adult Swim animated series The Venture Bros. is a tribute to Thompson, as they have a similar name, mannerisms, and physical appearance.[108][109]

- In the Cameron Crowe film Almost Famous, based on Crowe's experiences writing for Rolling Stone while on the road with the fictional band Stillwater", the writer is on the phone with an actor portraying Jann Wenner. Wenner tells the young journalist that he "is not there to join the party, we already have one Hunter Thompson" after the young writer amassed large hotel and traveling expenses and is overheard to be sharing his room with several young women.[110][111]

- Eric C. Shoaf donated a caché of approximately 800 items (in librarian terms, about 35–40 linear feet of material on a shelf) pertaining to the life and career of Thompson to the University of California at Santa Cruz.[112] Shoaf also published a descriptive bibliography, Gonzology: A Hunter Thompson Bibliography, of the works of Hunter S. Thompson with over 1,000 entries, many never before documented appearances in print, hundreds of biographical entries about Thompson's life, full descriptions of all his primary works, preface by William McKeen, Phd, and photo section with rare and exclusive items depicted.[113]

- An imaginary version of Thompson, played by P.J. Sosko, is a recurring character in the television series The Girls on the Bus (2024). He turns up to advise the young journalist Sadie McCarthy, who is a great admirer of Thompson and the only person who sees and hears him.[114]

References

[edit]- ^ Paul Scanlon (2009). Introduction. Fear and Loathing at Rolling Stone: The Essential Writing of Hunter S. Thompson. By Hunter S. Thompson. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4391-6595-9.

The notes were always signed: OK/HST.

- ^ "Obituary: Hunter S Thompson". BBC News. February 21, 2005. Archived from the original on August 25, 2017. Retrieved August 3, 2012.

- ^ "Hunter S Thompson: in his own words". The Guardian. February 21, 2005. Archived from the original on August 23, 2021. Retrieved August 23, 2021.

- ^ Kunzru, Hari (October 15, 1998). "Hari Kunzru reviews 'The Rum Diary' by Hunter S. Thompson and 'The Proud Highway' by Hunter S. Thompson, edited by Douglas Brinkley · LRB 15 October 1998". London Review of Books. Lrb.co.uk. pp. 33–34. Archived from the original on July 5, 2017. Retrieved October 11, 2012.

- ^ Reitwiesner, William Addams. "Ancestry of Hunter Thompson". Archived from the original on August 3, 2020. Retrieved August 3, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f Whitmer, Peter O. (1993). When The Going Gets Weird: The Twisted Life and Times of Hunter S. Thompson (First ed.). Hyperion. pp. 23–27. ISBN 1-56282-856-8.

- ^ Lezard, Nicholas (October 11, 1997). "An outlaw comes home". The Guardian.

- ^ a b c d McKeen, William (July 13, 2009). Outlaw Journalist: The Life and Times of Hunter S. Thompson. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 9780393249118.

Prestly Stockton Ray.

- ^ Eblen, Tom. "For sale: Hunter S. Thompson's childhood home – bullet holes, Gates of Hell not included". The Bluegrass and Beyond. Archived from the original on March 25, 2012. Retrieved August 3, 2012.

- ^ Hunter S Thompson Biography and Notes. "Books by Hunter S. Thompson – biography and notes". Biblio.com. Archived from the original on August 24, 2013. Retrieved July 30, 2010.

- ^ a b William McKeen (2008). Outlaw Journalist: The Life and Times of Hunter S. Thompson. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 9. ISBN 978-0393061925.

- ^ "Sue Grafton". carnegiecenterlex.org. Archived from the original on April 19, 2024. Retrieved September 14, 2024.

- ^ McKeen (2008). Outlaw Journalist. Norton. p. 5. ISBN 9780393061925.

- ^ Wenner, Jann; Seymour, Corey (September 4, 2008). Gonzo: The Life Of Hunter S. Thompson. Little, Brown Book Group. ISBN 978-0-7481-0849-7. Archived from the original on January 27, 2024. Retrieved October 2, 2020. Chapter 1, section by Lou Ann Iler.

- ^ a b Homberger, Eric (February 22, 2005). "Obituary: Hunter S. Thompson: Colourful chronicler of American life whose 'gonzo' journalism contrived to put him always at the centre of the action". The Guardian. Archived from the original on November 30, 2016. Retrieved December 11, 2016.

- ^ "Thompson, Hunter S." American National Biography Online. Archived from the original on May 7, 2017. Retrieved August 3, 2012.

- ^ Perry, Paul (2004). Fear and Loathing: The Strange and Terrible Saga of Hunter S. Thompson (2 ed.). Da Capo Press. p. 28. ISBN 1-56025-605-2.

- ^ Thompson, Hunter (2002). Songs of the Doomed (Reprint ed.). Simon & Schuster. pp. 29–32. ISBN 0-7432-4099-5.

- ^ a b "Columbia University scholarship for veterans to be named for Hunter S. Thompson, says wife". aspentimes.com. July 18, 2016. Archived from the original on June 22, 2020. Retrieved June 19, 2020.

- ^ Wills, David S. (2022). High White Notes: The Rise and Fall of Gonzo Journalism. Scotland: Beatdom Books. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-9934099-8-1.

- ^ a b Thompson, Hunter (1998). Douglas Brinkley (ed.). The Proud Highway: Saga of a Desperate Southern Gentleman (1st ed.). Ballantine Books. p. 139. ISBN 0-345-37796-6.

- ^ "Hunter S. Thompson: 'Proud Highway' (audio)". NPR. August 7, 1997. Archived from the original on October 4, 2013. Retrieved August 3, 2012.

- ^ "William Kennedy Biography". Archived from the original on February 8, 2012. Retrieved August 3, 2012.

- ^ Wills, David S. (2021). High White Notes: The Rise and Fall of Gonzo Journalism. Edinburgh: Beatdom Books. p. 90. ISBN 978-0993409981.

- ^ Perry, Paul (1992). Fear and Loathing: The Strange and Terrible Saga of Hunter S. Thompson (First Trade Paperback Printing 1993 ed.). Thunder's Mouth Press. pp. 59–61. ISBN 1-56025-065-8.

- ^ Kevin, Brian. "Before Gonzo: Hunter S. Thompson's Early, Underrated Journalism Career". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on October 6, 2017. Retrieved October 6, 2017.

- ^ "Author Bio for Stories I Tell Myself". Penguin Random House. Archived from the original on April 12, 2023. Retrieved April 12, 2023.

JUAN F. THOMPSON was born in 1964 outside of San Francisco, California, and grew up in Woody Creek, Colorado.

- ^ Parker, James (November 10, 2019). "Hunter S. Thompson's Letters to His Enemies". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on April 6, 2023. Retrieved April 6, 2023.

- ^ Brinkley, Douglas (March 10, 2005). "The Final Days at Owl Farm". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on October 18, 2007. Retrieved August 3, 2012.

- ^ Brinkley, Douglas or Sadler, Shelby. Thompson, Hunter (2000). Douglas Brinkley (ed.). Fear and Loathing in America (1st ed.). Simon & Schuster. p. 784. ISBN 0-684-87315-X. Introduction to letter to Tom Wolfe, p. 43.

- ^ Louison, Cole. "This is skag folks, pure skag: Hunter Thompson". Buzzsaw Haircut. Ithaca.edu. Archived from the original on September 3, 2006. Retrieved August 3, 2012.

- ^ a b Joseph, Jennifer (December 22, 2018). "The Haight-Ashbury's History and Heyday: How the 'Ground Zero of Hippiedom' Happened". The Battery. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved August 15, 2020.

- ^ "On the Wild Side". archive.nytimes.com. Archived from the original on September 1, 2021. Retrieved September 1, 2021.

- ^ "The Night Hunter S. Thompson Got Stomped by Hells Angels". OZY. January 12, 2017. Archived from the original on September 1, 2021. Retrieved September 1, 2021.

- ^ "RetroBites: Hunter S. Thompson & Hell's Angels (1967)". Youtube. CBC. July 7, 2010. Archived from the original on October 29, 2021. Retrieved August 3, 2012.

- ^ Fremont-Smith, Eliot (February 23, 1967), "Books of The Times; Motorcycle Misfits—Fiction and Fact." The New York Times, p. 33.

- ^ "Hunter S. Thompson | American journalist". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on October 6, 2017. Retrieved October 6, 2017.

- ^ Thompson, Hunter (May 14, 1967). "The Hashbury is the Capital of the Hippies". The New York Times Magazine. p. 29.

- ^ Thompson, Hunter (2006). Fear and Loathing in America (Paperback ed.). Simon & Schuster. p. 784. ISBN 978-0-684-87316-9.

- ^ Perry, Paul (2009). Fear and Loathing: The Strange and Terrible Saga of Hunter S. Thompson. London: Plexus. p. 115. ISBN 978-0-85965-429-6.

- ^ "Writers and Editors War Tax Protest", New York Post, January 30, 1968.

- ^ McKeen, William (2008). Outlaw Journalist: The Life and Times of Hunter S. Thompson. New York: W.W. Norton. p. 125. ISBN 9780393061925.

- ^ Thompson, Hunter (2001). Fear and Loathing in America (2nd ed.). Simon & Schuster. p. 784. ISBN 978-0-684-87316-9.

- ^ Peter Richardson, Savage Journey: Hunter S. Thompson and the Weird Road to Gonzo. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2022. ISBN 9780520304925

- ^ Gilbert, Sophie (June 26, 2014). "When Hunter S. Thompson Ran for Sheriff of Aspen". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on March 26, 2018. Retrieved March 25, 2018.

- ^ a b Anson, Robert Sam (December 10, 1970), "Rolling Stone, Part 2; Hunter Thompson Meets Fear and Loathing Face to Face", New Times

- ^ Hunter S. Thompson (2003), Kingdom of Fear, Simon & Schuster, p. 95.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Wenner, Jan (2022). Like A Rolling Stone: A Memoir (1st ed.). Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 9780316415194.

- ^ Martin, Douglas (March 16, 2006). "Bill Cardoso, 68, Editor Who Coined 'Gonzo', Is Dead". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 23, 2013. Retrieved August 3, 2012.

- ^ Thompson, Hunter (1979). The Great Shark Hunt: Strange Tales from a Strange Time (1st ed.). Summit Books. pp. 105–109. ISBN 0-671-40046-0.

- ^ Woods, Crawford (July 23, 1972). "Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 3, 2013. Retrieved August 3, 2012.

- ^ Kate Dundon (2019). "Guide to the Eric C. Shoaf Collection on Hunter S. Thompson". Online Archive of California. University of California, Santa Cruz. Archived from the original on April 13, 2023. Retrieved April 13, 2023.

- ^ Dickstein, Morris (1977). Gates of Eden: American Culture in the Sixties. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0465026319. Archived from the original on October 15, 2023. Retrieved April 13, 2023.

- ^ "Gonzo: The Life and Work of Dr. Hunter S. Thompson". Archived from the original on April 7, 2014. Retrieved April 4, 2014.

- ^ Wills, David S. (2021). High White Notes: The Rise and Fall of Gonzo Journalism. Edinburgh: Beatdom Books. pp. 337–339. ISBN 978-0993409981.

- ^ a b c Wills, David S. (2022). High White Notes: The Rise and Fall of Gonzo Journalism. Scotland: Beatdom Books. p. 359. ISBN 978-0-9934099-8-1.

- ^ The Great Thompson Hunt — Books — The Curse of Lono. Gonzo.org. Archived from the original on June 4, 2009. Retrieved July 13, 2009.

- ^ Whitmer, Peter O. (1993). When the Going Gets Weird. New York: Hyperion. p. 260.

- ^ Wills, David S. (2021). High White Notes: The Rise and Fall of Gonzo Journalism. Edinburgh: Beatdom Books. p. 406. ISBN 978-0993409981.

- ^ Thompson, Hunter S. (July 21, 1983). "Hunter S. Thompson: A Dog Took My Place". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on December 12, 2022. Retrieved December 12, 2022.

- ^ Wills, David S. (2021). High White Notes: The Rise and Fall of Gonzo Journalism. Edinburgh: Beatdom Books. p. 417. ISBN 978-0993409981.

- ^ Schevitz, Terry (February 5, 2005). "HUNTER S. THOMPSON: 1937–2005 / Original gonzo journalist kills self at age 67 / 'Fear and Loathing' author, ex-columnist for S.F. Examiner dies of gunshot wound". The San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on October 25, 2012. Retrieved June 1, 2018.

- ^ Nybergh, Thomas (February 9, 2015). "Stuck in Bat Country: The roller coaster career of Hunter S. Thompson". WhizzPast. Archived from the original on October 9, 2023. Retrieved September 23, 2023.

- ^ Morain, Dan (April 23, 1990). "Gonzo Time: Hunter Thompson, Facing Drug, Sexual Assault Charges, Claims He's the Victim of 'Witch Hunt'". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on May 31, 2022. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- ^ Victory for Hunter Thompson Archived April 12, 2020, at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times, May 31, 1990

- ^ a b T., Marlene. "Transcript of Hunter S. Thompson Interview". The Book Report. Archived from the original on December 30, 2012. Retrieved August 3, 2012.

- ^ "Rolling Stone". June 5, 2009. Archived from the original on September 16, 2016. Retrieved August 11, 2016.

- ^ Thompson, Hunter S. (June 17, 1994). "He Was a Crook". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on June 7, 2017. Retrieved March 7, 2017.

- ^ "Combined Records Department—Law Incident Table". The Smoking Gun. March 2, 2005. Archived from the original on June 30, 2012. Retrieved August 3, 2012.

- ^ "Citizen Thompson — Police report of death scene reveals gonzo journalist's "rosebud"". The Smoking Gun. September 8, 2005. Archived from the original on October 10, 2010. Retrieved October 13, 2008.

- ^ Douglas Brinkley (September 8, 2005). "Football Season Is Over Dr. Hunter S. Thompson's final note ... Entering the no more fun zone". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on June 19, 2008. Retrieved October 13, 2008.

- ^ Steadman, Ralph (February 2005). "Hunter S. Thompson 1937–2005". Ralphsteadman.com. Archived from the original on December 16, 2011.

- ^ a b "Hunter Thompson Blown Sky High". Billboard. Archived from the original on June 10, 2011. Retrieved July 30, 2010.

- ^ Brooks, Patricia; Brooks, Jonathan (2006). Laid to Rest in California: A Guide to the Cemeteries and Grave Sites of the Rich and Famous. p. 321.

- ^ a b Wolfe, Tom (February 22, 2005). "As Gonzo in Life as in His Work". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on February 22, 2005. Retrieved August 3, 2012.

- ^ Hunter S. Thompson (August 22, 1995). Better Than Sex. Random House. Archived from the original on April 15, 2022. Retrieved July 30, 2010.

- ^ a b Love, Robert. (May–June 2005) "A Technical Guide For Editing Gonzo". Columbia Journalism Review. May–June 2005. Archived from the original on April 10, 2007. Retrieved June 18, 2024.

- ^ Kaul, Arthur J. "Hunter S. Thompson". web.english.upenn.edu. Archived from the original on October 29, 2023. Retrieved October 30, 2023.

- ^ Johnston, Ian (February 17, 2011). "A Quietus Interview – An Unpublished Interview With Hunter S. Thompson". The Quietus. Archived from the original on January 27, 2024. Retrieved October 30, 2023.

- ^ Cohen, Rich (April 17, 2005). "Gonzo Nights". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 23, 2013. Retrieved February 9, 2017.

- ^ "Hunter S. Thompson (2/23/05)". December 26, 2006. December 27, 2006. Archived from the original on April 2, 2012. Retrieved August 3, 2012.

- ^ Clifford, Peggy (March 2, 2005). "Love Song for Hunter S. Thompson/18706". Archived from the original on April 2, 2012. Retrieved August 3, 2012.

- ^ "Fear And Loathing in Gonzovision". October 15, 2007. Archived from the original on March 30, 2012. Retrieved August 3, 2012.

- ^ "Hunter S. Thompson Halloween". October 31, 2006. Archived from the original on October 1, 2002. Retrieved July 30, 2010.

- ^ Glassie, John (February 3, 2003). "Hunter S. Thompson". Salon. Archived from the original on June 7, 2011. Retrieved August 3, 2012.

- ^ Susman, Tina (February 22, 2005). "Writer's suicide shocks friends". Newsday.com. Archived from the original on November 27, 2007. Retrieved August 3, 2012.

- ^ Higgins, Matt (September 2, 2003). "The Gonzo King". High Times. Archived from the original on September 29, 2012. Retrieved August 3, 2012.

- ^ McMaken, Ryan. "Hunter S. Thompson's Last Stand". Archived from the original on March 13, 2014. Retrieved August 3, 2012.

- ^ Moseley, Matt (April 26, 2006). "Lisl Released from Tooley Hall". lisl.com. Archived from the original on May 6, 2006. Retrieved March 14, 2017.

- ^ "Aspen Legal Seminar". Archived from the original on October 12, 2011. Retrieved August 3, 2012.

- ^ Hunter S. Thompson The Proud Highway: 1955–67, Saga of a Desperate Southern Gentleman, p. 509.

- ^ Hunter S. Thompson The Proud Highway, p. 493.

- ^ Hunter S. Thompson The Proud Highway, p. 456.

- ^ Hunter S. Thompson: The Movie by Alex Gibney, The Sunday Times, December 14, 2008

- ^ Hunter S. Thompson, The Great Shark Hunt (London, 1980), pp. 43–51.

- ^ Hunter S. Thompson, The Great Shark Hunt, (1980), pp. 44–50.

- ^ Bulger, Adam (March 9, 2004). "The Hunter S. Thompson Interview". FreezerBox. Archived from the original on January 25, 2021. Retrieved August 3, 2012.

- ^ Thompson, Hunter S. (October 24, 2004). "Fear and Loathing, Campaign 2004". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on July 9, 2008. Retrieved August 3, 2012.

- ^ Travers, Andrew (November 27, 2016). "What's next for Hunter S. Thompson's Owl Farm?". aspentimes.com. Archived from the original on June 22, 2020. Retrieved June 19, 2020.

- ^ "CI: Gonzo Foundation Scholarship Fund". ci.uky.edu. Archived from the original on June 21, 2020. Retrieved June 19, 2020.

- ^ "Hunter S. Thompson's Cabin Is on Airbnb — Proceeds Go To Columbia University Veterans". NBC New York. July 12, 2019. Archived from the original on June 22, 2020. Retrieved June 19, 2020.

- ^ I've personally assisted in all aspects of this scholarship. Lauren Maytin, Aspen, NLC longest-serving member has been involved since the inception of this prestigious award.

- ^ Whitehead, Ron (March 11, 2005). "Hunter S. Thompson, Kentucky Colonel". Reykjaviks Magazine. Archived from the original on June 12, 2013.

- ^ Whittaker, Richard (2023). "Johnny Hardwick, the Voice of Dale Gribble, Dies at 64". austinchronicle.com. Archived from the original on August 17, 2023. Retrieved March 23, 2024.

Hardwick described the character's look as being inspired by William S. Burroughs and Hunter S. Thompson

- ^ "Hunter S. Thompson dead at 67". CNN. Atlanta, Georgia: Turner Broadcasting Systems. February 21, 2005. Archived from the original on March 16, 2008. Retrieved November 29, 2024.

In later years, however, Thompson said he had made peace with the 'Uncle Duke' portrayal."I got used to it a long time ago," he told Freezerbox magazine in 2003. " I used to be a little perturbed by it. It was a lot more personal ... It no longer bothers me."

- ^ Video on YouTube

- ^ "2006 Rolling Stone Covers; RS 1000–1001 (May 18 – June 1, 2006)". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on April 27, 2012. Retrieved March 14, 2017.

- ^ "Cultelevision – The Venture Brothers". Den of Geek. September 24, 2008. Archived from the original on September 1, 2021. Retrieved September 1, 2021.

- ^ Maher, John (August 9, 2018). "Jackson Publick on the Ambition of 'The Venture Bros.'". The Dot and Line. Archived from the original on March 26, 2021. Retrieved September 1, 2021.

- ^ Handler, Rachel (June 24, 2020). "The Bittersweet Experience of Watching Almost Famous 20 Years On". Vulture. Archived from the original on September 1, 2021. Retrieved September 1, 2021.

- ^ "15 Secrets Revealed About Cameron Crowe's 'Almost Famous' on Its 15th Anniversary". TheWrap. September 17, 2015. Archived from the original on September 1, 2021. Retrieved September 1, 2021.

- ^ Baine, Wallace (February 27, 2019). "Fear and Loathing in Santa Cruz". Good Times Santa Cruz. Archived from the original on December 30, 2021. Retrieved December 30, 2021.

- ^ Shoaf, Eric C. (2018). Gonzology: a Hunter Thompson bibliography. Charlotte, NC: Cielo Publishing. ISBN 978-1-7324515-0-6. OCLC 1050361234.

- ^ Laguerre-Lewis, Kayla (March 13, 2024). "The Girls On The Bus Cast & Character Guide". Screenrant. Archived from the original on March 18, 2024. Retrieved April 29, 2024.

Further reading

[edit]- Denevi, Timothy, Freak Kingdom: Hunter S. Thompson's Manic Ten-Year Crusade Against American Fascism Archived October 9, 2023, at the Wayback Machine. New York: PublicAffairs, 2018. ISBN 1541767942

- McKeen, William, Outlaw Journalist: The Life and Times of Hunter S. Thompson Archived October 9, 2023, at the Wayback Machine. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2008. ISBN 0393335453

- Richardson, Peter, Savage Journey: Hunter S. Thompson and the Weird Road to Gonzo Archived April 2, 2023, at the Wayback Machine. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2022. ISBN 9780520304925

- Wills, David S., High White Notes: The Rise and Fall of Gonzo Journalism Archived April 14, 2023, at the Wayback Machine. Edinburgh: Beatdom Books, 2022. ISBN 978-0-9934099-8-1

- Wenner, Jann S.; Seymour, Corey, eds. (September 4, 2008). Gonzo: The Life of Hunter S. Thompson. New York: Little, Brown, and Co. ISBN 9780748108497. Archived from the original on January 27, 2024. Retrieved October 2, 2020.

External links

[edit]- Appearances on C-SPAN

- Hunter S. Thompson at IMDb

- Official author's page Archived September 7, 2023, at the Wayback Machine at Simon & Schuster

- Douglas Brinkley, Terry McDonell (Fall 2000). "Hunter S. Thompson, The Art of Journalism No. 1". The Paris Review. Fall 2000 (156). Archived from the original on May 7, 2024. Retrieved May 7, 2024.

- "Hunter S. Thompson's ESPN Page 2 Archive" Archived May 7, 2024, at the Wayback Machine, at Totallygonzo.org

- Hunter S. Thompson full bibliography Archived September 7, 2023, at the Wayback Machine, at Gonzo-Studies.org

- A collection of Hunter S. Thompson resources Archived September 22, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, at HSTbooks.org

- Hunter S. Thompson

- 1937 births

- 2005 suicides

- 2005 deaths

- 20th-century American journalists

- 20th-century American male writers

- 20th-century American novelists

- 20th-century American essayists

- 21st-century American journalists

- 21st-century American male writers

- 21st-century American novelists

- 9/11 conspiracy theorists

- American activist journalists

- American columnists

- American conspiracy theorists

- American male essayists

- American male journalists

- American male novelists

- American Marxists

- American people of Scottish descent

- American political writers

- American tax resisters

- Atherton High School alumni

- Columbia University School of General Studies alumni

- Counterculture of the 1960s

- Counterculture of the 1970s

- American psychedelic drug advocates

- Florida State University alumni

- Journalists from Colorado

- Journalists from Kentucky

- Louisville Male High School alumni

- Military personnel from Louisville, Kentucky

- Motorcycling writers

- Novelists from Colorado

- Novelists from Kentucky

- People from Glen Ellen, California

- Sportswriters from California

- Suicides by firearm in Colorado

- United States Air Force airmen

- Writers from Louisville, Kentucky