Mahabharata

| Mahabharata | |

|---|---|

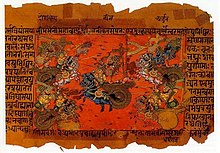

Manuscript illustration of the Battle of Kurukshetra | |

| Information | |

| Religion | Hinduism |

| Author | Vyasa |

| Language | Sanskrit |

| Period | Principally compiled in 3rd century BCE–4th century CE |

| Chapters | 18 Parvas |

| Verses | 200,000 |

| Full text | |

| Part of a series on |

| Hindu scriptures and texts |

|---|

|

| Related Hindu texts |

The Mahābhārata (/məˌhɑːˈbɑːrətə, ˌmɑːhə-/ mə-HAH-BAR-ə-tə, MAH-hə-;[1][2][3][4] Sanskrit: महाभारतम्, IAST: Mahābhāratam, pronounced [mɐɦaːˈbʱaːrɐt̪ɐm]) is one of the two major Smriti texts and Sanskrit epics of ancient India revered in Hinduism, the other being the Rāmāyaṇa.[5] It narrates the events and aftermath of the Kurukshetra War, a war of succession between two groups of princely cousins, the Kauravas and the Pāṇḍavas.

| Part of a series on |

| Hindu mythology |

|---|

|

| Sources |

| Cosmology |

| Deities |

| Personalities of the Epics |

| Hinduism Portal |

It also contains philosophical and devotional material, such as a discussion of the four "goals of life" or puruṣārtha (12.161). Among the principal works and stories in the Mahābhārata are the Bhagavad Gita, the story of Damayanti, the story of Shakuntala, the story of Pururava and Urvashi, the story of Savitri and Satyavan, the story of Kacha and Devayani, the story of Rishyasringa and an abbreviated version of the Rāmāyaṇa, often considered as works in their own right.

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of India |

|---|

|

Traditionally, the authorship of the Mahābhārata is attributed to Vyāsa. There have been many attempts to unravel its historical growth and compositional layers. The bulk of the Mahābhārata was probably compiled between the 3rd century BCE and the 3rd century CE, with the oldest preserved parts not much older than around 400 BCE.[6][7] The text probably reached its final form by the early Gupta period (c. 4th century CE).[8][9]

The title is translated as "Great Bharat (India)", or "the story of the great descendents of Bharata", or as "The Great Indian Tale".[10][11] The Mahābhārata is the longest epic poem known and has been described as "the longest poem ever written".[12][13] Its longest version consists of over 100,000 śloka or over 200,000 individual verse lines (each shloka is a couplet), and long prose passages. At about 1.8 million words in total, the Mahābhārata is roughly ten times the length of the Iliad and the Odyssey combined, or about four times the length of the Rāmāyaṇa.[14][15] Within the Indian tradition it is sometimes called the fifth Veda.[16]

Textual history and structure

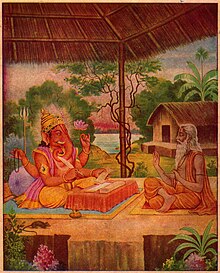

The epic is traditionally ascribed to the sage Vyasa, who is also a major figure in the epic.[12] Vyasa described it as being an itihasa (transl. history). He also describes the Guru–shishya tradition, which traces all great teachers and their students of the Vedic times.

The first section of the Mahābhārata states that it was Ganesha who wrote down the text to Vyasa's dictation, but this is regarded by scholars as a later interpolation to the epic and the "Critical Edition" does not include Ganesha.[17]

The epic employs the story within a story structure, otherwise known as frametales, popular in many Indian religious and non-religious works. It is first recited at Takshashila by the sage Vaisampayana,[18][19] a disciple of Vyasa, to the King Janamejaya who was the great-grandson of the Pandava prince Arjuna. The story is then recited again by a professional storyteller named Ugrashrava Sauti, many years later, to an assemblage of sages performing the 12-year sacrifice for the king Saunaka Kulapati in the Naimisha Forest.

The text was described by some early 20th-century Indologists as unstructured and chaotic. Hermann Oldenberg supposed that the original poem must once have carried an immense "tragic force" but dismissed the full text as a "horrible chaos."[20] Moritz Winternitz (Geschichte der indischen Literatur 1909) considered that "only unpoetical theologists and clumsy scribes" could have lumped the parts of disparate origin into an unordered whole.[21]

Accretion and redaction

Research on the Mahābhārata has put an enormous effort into recognizing and dating layers within the text. Some elements of the present Mahabharata can be traced back to Vedic times.[22] The background to the Mahābhārata suggests the origin of the epic occurs "after the very early Vedic period" and before "the first Indian 'empire' was to rise in the third century B.C." That this is "a date not too far removed from the 8th or 9th century B.C."[7][23] is likely. The Mahabharata started as an orally-transmitted tale of the charioteer bards.[24] It is generally agreed that "Unlike the Vedas, which have to be preserved letter-perfect, the epic was a popular work whose reciters would inevitably conform to changes in language and style,"[23] so the earliest 'surviving' components of this dynamic text are believed to be no older than the earliest 'external' references we have to the epic, which include an reference in Panini's 4th century BCE grammar Ashtadhyayi 4:2:56.[7][23] Vishnu Sukthankar, editor of the first great critical edition of the Mahābhārata, commented: "It is useless to think of reconstructing a fluid text in an original shape, based on an archetype and a stemma codicum. What then is possible? Our objective can only be to reconstruct the oldest form of the text which it is possible to reach based on the manuscript material available."[25] That manuscript evidence is somewhat late, given its material composition and the climate of India, but it is very extensive.

The Mahābhārata itself (1.1.61) distinguishes a core portion of 24,000 verses: the Bhārata proper, as opposed to additional secondary material, while the Ashvalayana Grihyasutra (3.4.4) makes a similar distinction. At least three redactions of the text are commonly recognized: Jaya (Victory) with 8,800 verses attributed to Vyasa, the Bharata with 24,000 verses as recited by Vaisampayana, and finally the Mahābhārata as recited by Ugrashrava Sauti with over 100,000 verses.[26][27] However, some scholars, such as John Brockington, argue that Jaya and Bharata refer to the same text, and ascribe the theory of Jaya with 8,800 verses to a misreading of a verse in the Adi Parva (1.1.81).[28] The redaction of this large body of text was carried out after formal principles, emphasizing the numbers 18[29] and 12. The addition of the latest parts may be dated by the absence of the Anushasana Parva and the Virata Parva from the "Spitzer manuscript".[30] The oldest surviving Sanskrit text dates to the Kushan Period (200 CE).[31]

According to what one figure says at Mbh. 1.1.50, there were three versions of the epic, beginning with Manu (1.1.27), Astika (1.3, sub-Parva 5), or Vasu (1.57), respectively. These versions would correspond to the addition of one and then another 'frame' settings of dialogues. The Vasu version would omit the frame settings and begin with the account of the birth of Vyasa. The astika version would add the sarpasattra and ashvamedha material from Brahmanical literature, introduce the name Mahābhārata, and identify Vyasa as the work's author. The redactors of these additions were probably Pancharatrin scholars who according to Oberlies (1998) likely retained control over the text until its final redaction. Mention of the Huna in the Bhishma Parva however appears to imply that this Parva may have been edited around the 4th century.[32]

The Adi Parva includes the snake sacrifice (sarpasattra) of Janamejaya, explaining its motivation, detailing why all snakes in existence were intended to be destroyed, and why despite this, there are still snakes in existence. This sarpasattra material was often considered an independent tale added to a version of the Mahābhārata by "thematic attraction" (Minkowski 1991), and considered to have a particularly close connection to Vedic (Brahmana) literature. The Panchavimsha Brahmana (at 25.15.3) enumerates the officiant priests of a sarpasattra among whom the names Dhritarashtra and Janamejaya, two main figures of the Mahābhārata's sarpasattra, as well as Takshaka, a snake in the Mahābhārata, occur.[33]

The Suparnakhyana, a late Vedic period poem considered to be among the "earliest traces of epic poetry in India," is an older, shorter precursor to the expanded legend of Garuda that is included in the Astika Parva, within the Adi Parva of the Mahābhārata.[34][35]

Historical references

The earliest known references to bhārata and the compound mahābhārata date to the Ashtadhyayi (sutra 6.2.38)[36] of Panini (fl. 4th century BCE) and the Ashvalayana Grihyasutra (3.4.4). This may mean that the core 24,000 verses, known as the Bhārata, as well as an early version of the extended Mahābhārata, were composed by the 4th century BCE. However, it is uncertain whether Panini referred to the epic, as bhārata was also used to describe other things. Albrecht Weber mentions the Rigvedic tribe of the Bharatas, where a great person might have been designated as Mahā-Bhārata. However, as Panini also mentions figures that play a role in the Mahābhārata, some parts of the epic may have already been known in his day. Another aspect is that Panini determined the accent of mahā-bhārata. However, the Mahābhārata was not recited in Vedic accent.[37]

The Greek writer Dio Chrysostom (c. 40 – c. 120 CE) reported that Homer's poetry was being sung even in India.[38] Many scholars have taken this as evidence for the existence of a Māhabhārata at this date, whose episodes Dio or his sources identify with the story of the Iliad.[39]

Several stories within the Mahābhārata took on separate identities of their own in Classical Sanskrit literature. For instance, the Abhijnanashkuntala by the renowned Sanskrit poet Kalidasa (c. 400 CE), believed to have lived in the era of the Gupta dynasty, is based on a story that is the precursor to the Mahābhārata. The Urubhanga, a Sanskrit play written by Bhasa who is believed to have lived before Kalidasa, is based on the slaying of Duryodhana by the splitting of his thighs by Bhima.[40]

The copper-plate inscription of the Maharaja Sharvanatha (533–534 CE) from Khoh (Satna District, Madhya Pradesh) describes the Mahābhārata as a "collection of 100,000 verses" (śata-sahasri saṃhitā).[40]

The 18 parvas or books

The division into 18 parvas is as follows:

| Parva | Title | Sub-parvas | Contents |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Adi Parva (The Book of the Beginning) | 1–19 | How the Mahābhārata came to be narrated by Sauti to the assembled rishis at Naimisharanya, after having been recited at the sarpasattra of Janamejaya by Vaisampayana at Takshashila. The history and genealogy of the Bharata and Bhrigu races are recalled, as is the birth and early life of the Kuru princes (adi means first). Adi parva describes Pandava's birth, childhood, education, marriage, struggles due to conspiracy as well as glorious achievements. |

| 2 | Sabha Parva (The Book of the Assembly Hall) | 20–28 | Maya Danava erects the palace and court (sabha), at Indraprastha. The Sabha Parva narrates the glorious Yudhisthira's Rajasuya sacrifice performed with the help of his brothers and Yudhisthira's rule in Shakraprastha/Indraprastha as well as the humiliation and deceit caused by conspiracy along with their own action. |

| 3 | Vana Parva also Aranyaka Parva, Aranya Parva (The Book of the Forest) | 29–44 | The twelve years of exile in the forest (aranya). The entire Parva describes their struggle and consolidation of strength. |

| 4 | Virata Parva (The Book of Virata) | 45–48 | The year spent incognito at the court of Virata. A single warrior (Arjuna) defeated the entire Kuru army including Karna, Bhishma, Drona, Ashwatthama, etc. and recovered the cattle of the Virata kingdom.[41] |

| 5 | Udyoga Parva (The Book of the Effort) | 49–59 | Preparations for war and efforts to bring about peace between the Kaurava and the Pandava sides which eventually fail (udyoga means effort or work). |

| 6 | Bhishma Parva (The Book of Bhishma) | 60–64 | The first part of the great battle, with Bhishma as commander for the Kaurava and his fall on the bed of arrows. The most important aspect of Bhishma Parva is the Bhagavad Gita narrated by Krishna to Arjuna. (Includes the Bhagavad Gita in chapters 25–42.)[42][43] |

| 7 | Drona Parva (The Book of Drona) | 65–72 | The battle continues, with Drona as commander. This is the major book of the war. Most of the great warriors on both sides are dead by the end of this book. |

| 8 | Karna Parva (The Book of Karna) | 73 | The continuation of the battle with Karna as commander of the Kaurava forces. |

| 9 | Shalya Parva (The Book of Shalya) | 74–77 | The last day of the battle, with Shalya as commander. Also told in detail, is the pilgrimage of Balarama to the fords of the river Saraswati and the mace fight between Bhima and Duryodhana which ends the war, since Bhima kills Duryodhana by smashing him on the thighs with a mace. |

| 10 | Sauptika Parva (The Book of the Sleeping Warriors) | 78–80 | Ashwatthama, Kripa and Kritavarma kill the remaining Pandava army in their sleep. Only seven warriors remain on the Pandava side and three on the Kaurava side. |

| 11 | Stri Parva (The Book of the Women) | 81–85 | Gandhari and the women (stri) of the Kauravas and Pandavas lament the dead and Gandhari cursing Krishna for the massive destruction and the extermination of the Kaurava. |

| 12 | Shanti Parva (The Book of Peace) | 86–88 | The crowning of Yudhishthira as king of Hastinapura, and instructions from Bhishma for the newly anointed king on society, economics, and politics. This is the longest book of the Mahabharata. |

| 13 | Anushasana Parva (The Book of the Instructions) | 89–90 | The final instructions (anushasana) from Bhishma. This Parba contains the last day of Bhishma and his advice and wisdom to the upcoming emperor Yudhishthira. |

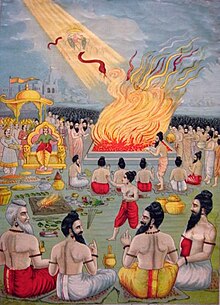

| 14 | Ashvamedhika Parva (The Book of the Horse Sacrifice)[44] | 91–92 | The royal ceremony of the Ashvamedha (Horse sacrifice) conducted by Yudhishthira. The world conquest by Arjuna. Anugita is told by Krishna to Arjuna. |

| 15 | Ashramavasika Parva (The Book of the Hermitage) | 93–95 | The eventual deaths of Dhritarashtra, Gandhari, and Kunti in a forest fire when they are living in a hermitage in the Himalayas. Vidura predeceases them and Sanjaya on Dhritarashtra's bidding goes to live in the higher Himalayas. |

| 16 | Mausala Parva (The Book of the Clubs) | 96 | The materialization of Gandhari's curse, i.e., the infighting between the Yadavas with maces (mausala) and the eventual destruction of the Yadavas. |

| 17 | Mahaprasthanika Parva (The Book of the Great Journey) | 97 | The great journey of Yudhishthira, his brothers, and his wife Draupadi across the whole country and finally their ascent of the great Himalayas where each Pandava falls except for Yudhishthira. |

| 18 | Svargarohana Parva (The Book of the Ascent to Heaven) | 98 | Yudhishthira's final test and the return of the Pandavas to the spiritual world (svarga). |

| khila | Harivamsa Parva (The Book of the Genealogy of Hari) | 99–100 | This is an addendum to the 18 books, and covers those parts of the life of Krishna which is not covered in the 18 parvas of the Mahabharata. |

Historical context

The historicity of the Kurukshetra War is unclear. Many historians estimate the date of the Kurukshetra war to Iron Age India of the 10th century BCE.[45] The setting of the epic has a historical precedent in Iron Age (Vedic) India, where the Kuru kingdom was the center of political power during roughly 1200 to 800 BCE.[46] A dynastic conflict of the period could have been the inspiration for the Jaya, the foundation on which the Mahābhārata corpus was built, with a climactic battle, eventually coming to be viewed as an epochal event.

Puranic literature presents genealogical lists associated with the Mahābhārata narrative. The evidence of the Puranas is of two kinds. Of the first kind, there is the direct statement that there were 1,015 (or 1,050) years between the birth of Parikshit (Arjuna's grandson) and the accession of Mahapadma Nanda (400–329 BCE), which would yield an estimate of about 1400 BCE for the Bharata battle.[47] However, this would imply improbably long reigns on average for the kings listed in the genealogies.[48] Of the second kind is analysis of parallel genealogies in the Puranas between the times of Adhisimakrishna (Parikshit's great-grandson) and Mahapadma Nanda. Pargiter accordingly estimated 26 generations by averaging 10 different dynastic lists and, assuming 18 years for the average duration of a reign, arrived at an estimate of 850 BCE for Adhisimakrishna, and thus approximately 950 BCE for the Bharata battle.[49]

B. B. Lal used the same approach with a more conservative assumption of the average reign to estimate a date of 836 BCE, and correlated this with archaeological evidence from Painted Grey Ware (PGW) sites, the association being strong between PGW artifacts and places mentioned in the epic.[50] John Keay suggests "their core narratives seem to relate to events from a period prior to all but the Rig Veda."[51]

Attempts to date the events using methods of archaeoastronomy have produced, depending on which passages are chosen and how they are interpreted, estimates ranging from the late 4th to the mid-2nd millennium BCE.[52] The late 4th-millennium date has a precedent in the calculation of the Kali Yuga epoch, based on planetary conjunctions, by Aryabhata (6th century). Aryabhata's date of 18 February 3102 BCE for Mahābhārata war has become widespread in Indian tradition. Some sources mark this as the disappearance of Krishna from the Earth.[53] The Aihole inscription of Pulakeshin II, dated to Saka 556 = 634 CE, claims that 3,735 years have elapsed since the Bhārata battle, putting the date of Mahābhārata war at 3137BCE.[54][55]

Another traditional school of astronomers and historians, represented by Vrddha Garga, Varāhamihira and Kalhana, place the Bharata war 653 years after the Kali Yuga epoch, corresponding to 2449 BCE.[56] According to Varāhamihira's Bṛhat Saṃhitā (6th century), Yudhishthara lived 2,526 years before the beginning of the Shaka era, which begins in the 78 CE. This places Yudhishthara (and therefore, the Mahabharata war) around 2448–2449 BCE (2526–78). Some scholars have attempted to identify the "Shaka" calendar era mentioned by Varāhamihira with other eras, but such identifications place Varāhamihira in the first century BCE, which is impossible as he refers to the 5th century astronomer Aryabhata. Kalhana's Rajatarangini (11th century), apparently relying on Varāhamihira, also states that the Pandavas flourished 653 years after the beginning of the Kali Yuga; Kalhana adds that people who believe that the Bharata war was fought at the end of the Dvapara Yuga are foolish.[57]

Synopsis

The core story of the work is that of a dynastic struggle for the throne of Hastinapura, the kingdom ruled by the Kuru clan. The two collateral branches of the family that participate in the struggle are the Kaurava and the Pandava. Although the Kaurava is the senior branch of the family, Duryodhana, the eldest Kaurava, is younger than Yudhishthira, the eldest Pandava. Both Duryodhana and Yudhishthira claim to be first in line to inherit the throne.

The struggle culminates in the Kurukshetra War, in which the Pandavas are ultimately victorious. The battle produces complex conflicts of kinship and friendship, instances of family loyalty and duty taking precedence over what is right, as well as the converse.

The Mahābhārata itself ends with the death of Krishna, and the subsequent end of his dynasty and ascent of the Pandava brothers to heaven. It also marks the beginning of the Hindu age of Kali Yuga, the fourth and final age of humankind, in which great values and noble ideas have crumbled, and people are heading towards the complete dissolution of right action, morality, and virtue.

The older generations

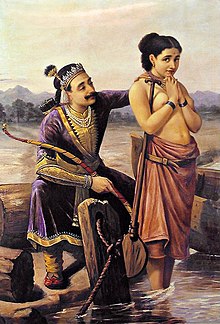

King Janamejaya's ancestor, Shantanu, the king of Hastinapura, had a short-lived marriage with the goddess Ganga and had a son, Devavrata (later to be called Bhishma, a great warrior), who becomes the heir apparent. Many years later, when King Shantanu goes hunting, he sees Satyavati, the daughter of the chief of fishermen, and asks her father for her hand. Her father refuses to consent to the marriage unless Shantanu promises to make any future son of Satyavati the king upon his death. To resolve his father's dilemma, Devavrata agrees to relinquish his right to the throne. As the fisherman is not sure about the prince's children honoring the promise, Devavrata also takes a vow of lifelong celibacy to guarantee his father's promise.

Shantanu has two sons by Satyavati, Chitrāngada and Vichitravirya. Upon Shantanu's death, Chitrangada becomes king. He lives a very short uneventful life and dies. Vichitravirya, the younger son, rules Hastinapura. Meanwhile, the King of Kāśī arranges a swayamvara for his three daughters, neglecting to invite the royal family of Hastinapur. To arrange the marriage of young Vichitravirya, Bhishma attends the swayamvara of the three princesses Amba, Ambika, and Ambalika, uninvited, and proceeds to abduct them. Ambika and Ambalika consent to be married to Vichitravirya.

The oldest princess Amba, however, informs Bhishma that she wishes to marry the king of Shalva whom Bhishma defeated at their swayamvara. Bhishma lets her leave to marry the king of Shalva, but Shalva refuses to marry her, still smarting at his humiliation at the hands of Bhishma. Amba then returns to marry Bhishma but he refuses due to his vow of celibacy. Amba becomes enraged and becomes Bhishma's bitter enemy, holding him responsible for her plight. She vows to kill him in her next life. Later she is reborn to King Drupada as Shikhandi (or Shikhandini) and causes Bhishma's fall, with the help of Arjuna, in the battle of Kurukshetra.

The Pandava and Kaurava princes

When Vichitravirya dies young without any heirs, Satyavati asks her first son Vyasa, born to her from a previous union with the sage Parashara, to father children with the widows. The eldest, Ambika, shuts her eyes when she sees him, and so her son Dhritarashtra is born blind. Ambalika turns pale and bloodless upon seeing him, and thus her son Pandu is born pale and unhealthy (the term Pandu may also mean 'jaundiced'[58]). Due to the physical challenges of the first two children, Satyavati asks Vyasa to try once again. However, Ambika and Ambalika send their maid instead, to Vyasa's room. Vyasa fathers a third son, Vidura, by the maid. He is born healthy and grows up to be one of the wisest figures in the Mahabharata. He serves as Prime Minister (Mahamantri or Mahatma) to King Pandu and King Dhritarashtra.

When the princes grow up, Dhritarashtra is about to be crowned king by Bhishma when Vidura intervenes and uses his knowledge of politics to assert that a blind person cannot be king. This is because a blind man cannot control and protect his subjects. The throne is then given to Pandu because of Dhritarashtra's blindness. Pandu marries twice, to Kunti and Madri. Dhritarashtra marries Gandhari, a princess from Gandhara, who blindfolds herself for the rest of her life so that she may feel the pain that her husband feels. Her brother Shakuni is enraged by this and vows to take revenge on the Kuru family. One day, when Pandu is relaxing in the forest, he hears the sound of a wild animal. He shoots an arrow in the direction of the sound. However, the arrow hits the sage Kindama, who was engaged in a sexual act in the guise of a deer. He curses Pandu that if he engages in a sexual act, he will die. Pandu then retires to the forest along with his two wives, and his brother Dhritarashtra rules thereafter, despite his blindness.

Pandu's older queen Kunti, however, had been given a boon by Sage Durvasa that she could invoke any god using a special mantra. Kunti uses this boon to ask Dharma, the god of justice, Vayu, the god of the wind, and Indra, the lord of the heavens for sons. She gives birth to three sons, Yudhishthira, Bhima, and Arjuna, through these gods. Kunti shares her mantra with the younger queen Madri, who bears the twins Nakula and Sahadeva through the Ashwini twins. However, Pandu and Madri indulge in lovemaking, and Pandu dies. Madri commits suicide out of remorse. Kunti raises the five brothers, who are from then on usually referred to as the Pandava brothers.

Dhritarashtra has a hundred sons, and one daughter—Duhsala—through Gandhari,[59] all born after the birth of Yudhishthira. These are the Kaurava brothers, the eldest being Duryodhana, and the second Dushasana. Other Kaurava brothers include Vikarna and Sukarna. The rivalry and enmity between them and the Pandava brothers, from their youth and into manhood, leads to the Kurukshetra war.

Lakshagraha (the house of lac)

After the deaths of their mother (Madri) and father (Pandu), the Pandavas and their mother Kunti return to the palace of Hastinapur. Yudhishthira is made Crown Prince by Dhritarashtra, under considerable pressure from his courtiers. Dhritarashtra wanted his son Duryodhana to become king and lets his ambition get in the way of preserving justice.

Shakuni, Duryodhana, and Dushasana plot to get rid of the Pandavas. Shakuni calls the architect Purochana to build a palace out of flammable materials like lac and ghee. He then arranges for the Pandavas and the Queen Mother Kunti to stay there, intending to set it alight. However, the Pandavas are warned by their wise uncle, Vidura, who sends them a miner to dig a tunnel. They escape to safety through the tunnel and go into hiding. During this time, Bhima marries a demoness Hidimbi and has a son Ghatotkacha. Back in Hastinapur, the Pandavas and Kunti are presumed dead.[60]

Marriage to Draupadi

Whilst they were in hiding, the Pandavas learn of a swayamvara which is taking place for the hand of the Pāñcāla princess Draupadī. The Pandavas, disguised as Brahmins, come to witness the event. Meanwhile, Krishna, who has already befriended Draupadi, tells her to look out for Arjuna (though now believed to be dead). The task was to string a mighty steel bow and shoot a target on the ceiling, which was the eye of a moving artificial fish, while looking at its reflection in oil below. In popular versions, after all the princes fail, many being unable to lift the bow, Karna proceeds to the attempt but is interrupted by Draupadi who refuses to marry a suta (this has been excised from the Critical Edition of Mahabharata[61][62] as later interpolation[63]). After this, the swayamvara is opened to the Brahmins leading Arjuna to win the contest and marry Draupadi. The Pandavas return home and inform their meditating mother that Arjuna has won a competition and to look at what they have brought back. Without looking, Kunti asks them to share whatever Arjuna has won amongst themselves, thinking it to be alms. Thus, Draupadi ends up being the wife of all five brothers.

Indraprastha

After the wedding, the Pandava brothers are invited back to Hastinapura. The Kuru family elders and relatives negotiate and broker a split of the kingdom, with the Pandavas obtaining and demanding only a wild forest inhabited by Takshaka, the king of snakes, and his family. Through hard work, the Pandavas build a new glorious capital for the territory at Indraprastha.

Shortly after this, Arjuna elopes with and then marries Krishna's sister, Subhadra. Yudhishthira wishes to establish his position as king; he seeks Krishna's advice. Krishna advises him, and after due preparation and the elimination of some opposition, Yudhishthira carries out the rājasūya yagna ceremony; he is thus recognized as pre-eminent among kings.

The Pandavas have a new palace built for them, by Maya the Danava.[64] They invite their Kaurava cousins to Indraprastha. Duryodhana walks round the palace, and mistakes a glossy floor for water, and will not step in. After being told of his error, he then sees a pond and assumes it is not water and falls in. Bhima, Arjuna, the twins and the servants laugh at him.[65] In popular adaptations, this insult is wrongly attributed to Draupadi, even though in the Sanskrit epic, it was the Pandavas (except Yudhishthira) who had insulted Duryodhana. Enraged by the insult, and jealous at seeing the wealth of the Pandavas, Duryodhana decides to host a dice-game on Shakuni's suggestion. This suggestion was accepted by Yudhisthira despite the rest of the Pandavas advising him not to play.

The dice game

Shakuni, Duryodhana's uncle, now arranges a dice game, playing against Yudhishthira with loaded dice. In the dice game, Yudhishthira loses all his wealth, then his kingdom. Yudhishthira then gambles his brothers, himself, and finally his wife into servitude. The jubilant Kauravas insult the Pandavas in their helpless state and even try to disrobe Draupadi in front of the entire court, but Draupadi's disrobe is prevented by Krishna, who miraculously make her dress endless, therefore it couldn't be removed.

Dhritarashtra, Bhishma, and the other elders are aghast at the situation, but Duryodhana is adamant that there is no place for two crown princes in Hastinapura. Against his wishes Dhritarashtra orders for another dice game. The Pandavas are required to go into exile for 12 years, and in the 13th year, they must remain hidden. If they are discovered by the Kauravas in the 13th year of their exile, then they will be forced into exile for another 12 years.

Exile and return

The Pandavas spend thirteen years in exile; many adventures occur during this time. The Pandavas acquire many divine weapons, given by gods, during this period. They also prepare alliances for a possible future conflict. They spend their final year in disguise in the court of the king Virata, and they are discovered just after the end of the year.

At the end of their exile, they try to negotiate a return to Indraprastha with Krishna as their emissary. However, this negotiation fails, because Duryodhana objected that they were discovered in the 13th year of their exile and the return of their kingdom was not agreed upon. Then the Pandavas fought the Kauravas, claiming their rights over Indraprastha.

The battle at Kurukshetra

The two sides summon vast armies to their help and line up at Kurukshetra for a war. The kingdoms of Panchala, Dwaraka, Kasi, Kekaya, Magadha, Matsya, Chedi, Pandyas, Telinga, and the Yadus of Mathura and some other clans like the Parama Kambojas were allied with the Pandavas. The allies of the Kauravas included the kings of Pragjyotisha, Anga, Kekaya, Sindhudesa (including Sindhus, Sauviras and Sivis), Mahishmati, Avanti in Madhyadesa, Madra, Gandhara, Bahlika people, Kambojas and many others. Before war was declared, Balarama had expressed his unhappiness at the developing conflict and leaves to go on pilgrimage; thus he does not take part in the battle itself. Krishna takes part in a non-combatant role, as charioteer (Sarathy) for Arjuna and offers Narayani Sena consisting of Abhira gopas to the Kauravas to fight on their side.[66][67]

Before the battle, Arjuna, noticing that the opposing army includes his cousins and relatives, including his grandfather Bhishma and his teacher Drona, has grave doubts about the fight. He falls into despair and refuses to fight. At this time, Krishna reminds him of his duty as a Kshatriya to fight for a righteous cause in the famous Bhagavad Gita section of the epic.

Though initially sticking to chivalrous notions of warfare, both sides soon adopt dishonorable tactics. At the end of the 18-day battle, only the Pandavas, Satyaki, Kripa, Ashwatthama, Kritavarma, Yuyutsu and Krishna survive. Yudhisthira becomes King of Hastinapur and Gandhari curses Krishna that the downfall of his clan is imminent. All of the warriors who died in the Kurukshetra war went to swarga.

The end of the Pandavas

After "seeing" the carnage, Gandhari, who had lost all her sons, curses Krishna to be a witness to a similar annihilation of his family, for though divine and capable of stopping the war, he had not done so. Krishna accepts the curse, which bears fruit 36 years later.

The Pandavas, who had ruled their kingdom meanwhile, decide to renounce everything. Clad in skins and rags they retire to the Himalaya and climb towards heaven in their bodily form. A stray dog travels with them. One by one the brothers and Draupadi fall on their way. As each one stumbles, Yudhishthira gives the rest the reason for their fall (Draupadi was partial to Arjuna, Nakula and Sahadeva were vain and proud of their looks, and Bhima and Arjuna were proud of their strength and archery skills, respectively). Only the virtuous Yudhishthira, who had tried everything to prevent the carnage, and the dog remain. The dog reveals himself to be the god Yama (also known as Yama Dharmaraja) and then takes him to the underworld where he sees his siblings and wife. After explaining the nature of the test, Yama takes Yudhishthira back to heaven and explains that it was necessary to expose him to the underworld because (Rajyante narakam dhruvam) any ruler has to visit the underworld at least once. Yama then assures him that his siblings and wife would join him in heaven after they had been exposed to the underworld for measures of time according to their vices.

Arjuna's grandson Parikshit rules after them and dies bitten by a snake. His furious son, Janamejaya, decides to perform a snake sacrifice (sarpasattra) to destroy the snakes. It is at this sacrifice that the tale of his ancestors is narrated to him.

The reunion

The Mahābhārata mentions that Karna, the Pandavas, Draupadi and Dhritarashtra's sons eventually ascended to svarga and "attained the state of the gods", and banded together – "serene and free from anger".[68]

Themes

Just war

The Mahābhārata offers one of the first instances of theorizing about dharmayuddha, "just war", illustrating many of the standards that would be debated later across the world. In the story, one of five brothers asks if the suffering caused by war can ever be justified. A long discussion ensues between the siblings, establishing criteria like proportionality (chariots cannot attack cavalry, only other chariots; no attacking people in distress), just means (no poisoned or barbed arrows), just cause (no attacking out of rage), and fair treatment of captives and the wounded.[69]

Translations, versions and derivative works

Translations

The first Bengali translations of the Mahabharata emerged in the 16th century. It is disputed whether Kavindra Parameshwar of Hooghly (based in Chittagong during his writing) or Sri Sanjay of Sylhet was the first to translate it into Bengali.[71][72]

A Persian translation of Mahabharata, titled Razmnameh, was produced at Akbar's orders, by Faizi and ʽAbd al-Qadir Badayuni in the 16th century.[73]

The first complete English translation was the Victorian prose version by Kisari Mohan Ganguli,[74] published between 1883 and 1896 (Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers) and by Manmatha Nath Dutt (Motilal Banarsidass Publishers). Most critics consider the translation by Ganguli to be faithful to the original text. The complete text of Ganguli's translation is in the public domain and is available online.[75][76]

An early poetry translation by Romesh Chunder Dutt and published in 1898 condenses the main themes of the Mahābhārata into English verse.[77] A later poetic "transcreation" (author's description) of the full epic into English, done by the poet P. Lal, is complete, and in 2005 began being published by Writers Workshop, Calcutta. The P. Lal translation is a non-rhyming verse-by-verse rendering, and is the only edition in any language to include all slokas in all recensions of the work (not just those in the Critical Edition). The completion of the publishing project is scheduled for 2010.[needs update] Sixteen of the eighteen volumes are now available. Dr. Pradip Bhattacharya stated that the P. Lal version is "known in academia as the 'vulgate'".[78] However, it has been described as "not strictly speaking a translation".[79]

A project to translate the full epic into English prose, translated by various hands, began to appear in 2005 from the Clay Sanskrit Library, published by New York University Press. The translation is based not on the Critical Edition but on the version known to the commentator Nīlakaṇṭha. Currently available are 15 volumes of the projected 32-volume edition.

Indian Vedic Scholar Shripad Damodar Satwalekar translated the Critical Edition of Mahabharata into Hindi[80] which was assigned to him by the Government of India. After his death, the task was taken up by Shrutisheel Sharma.[81][82][note 1]

Indian economist Bibek Debroy also wrote an unabridged English translation in ten volumes. Volume 1: Adi Parva was published in March 2010, and the last two volumes were published in December 2014. Abhinav Agarwal referred to Debroy's translation as "thoroughly enjoyable and impressively scholarly".[79] In a review of the seventh volume, Bhattacharya stated that the translator bridged gaps in the narrative of the Critical Edition, but also noted translation errors.[78] Gautam Chikermane of Hindustan Times wrote that where "both Debroy and Ganguli get tiresome is in the use of adjectives while describing protagonists".[83]

Another English prose translation of the full epic, based on the Critical Edition, is in progress, published by University of Chicago Press. It was initiated by Indologist J. A. B. van Buitenen (books 1–5) and, following a 20-year hiatus caused by the death of van Buitenen is being continued by several scholars. James L. Fitzgerald translated book 11 and the first half of book 12. David Gitomer is translating book 6, Gary Tubb is translating book 7, Christopher Minkowski is translating book 8, Alf Hiltebeitel is translating books 9 and 10, Fitzgerald is translating the second half of book 12, Patrick Olivelle is translating book 13, and Fred Smith is translating book 14–18.[84][85]

Many condensed versions, abridgments and novelistic prose retellings of the complete epic have been published in English, including works by Ramesh Menon, William Buck, R. K. Narayan, C. Rajagopalachari, Kamala Subramaniam, K. M. Munshi, Krishna Dharma Dasa, Purnaprajna Dasa, Romesh C. Dutt, Bharadvaja Sarma, John D. Smith and Sharon Maas.

Critical Edition

Between 1919 and 1966, scholars at the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, Pune, compared the various manuscripts of the epic from India and abroad and produced the Critical Edition of the Mahābhārata, on 13,000 pages in 19 volumes, over the span of 47 years, followed by the Harivamsha in another two volumes and six index volumes. This is the text that is usually used in current Mahābhārata studies for reference.[86] This work is sometimes called the "Pune" or "Poona" edition of the Mahabharata.

Regional versions

Many regional versions of the work developed over time, mostly differing only in minor details, or with verses or subsidiary stories being added. These include the Tamil street theatre, terukkuttu and kattaikkuttu, the plays of which use themes from the Tamil language versions of Mahābhārata, focusing on Draupadi.[87]

Outside the Indian subcontinent, in Indonesia, a version was developed in ancient Java as Kakawin Bhāratayuddha in the 11th century under the patronage of King Dharmawangsa (990–1016)[88] and later it spread to the neighboring island of Bali, which remains a Hindu majority island today. It has become the fertile source for Javanese literature, dance drama (wayang wong), and wayang shadow puppet performances. This Javanese version of the Mahābhārata differs slightly from the original Indian version.[note 2] Another notable difference is the inclusion of the Punakawans, the clown servants of the main figures in the storyline. These Semar, Petruk, Gareng, and Bagong, who are much-loved by Indonesian audiences. [citation needed] There are also some spin-off episodes developed in ancient Java, such as Arjunawiwaha composed in the 11th century.

A Kawi version of the Mahabharata, of which eight of the eighteen parvas survive, is found on the Indonesian island of Bali. It has been translated into English by Dr. I. Gusti Putu Phalgunadi.[89]

Derivative literature

Bhasa, the 2nd- or 3rd-century CE Sanskrit playwright, wrote two plays on episodes in the Marabharata, Urubhanga (Broken Thigh), about the fight between Duryodhana and Bhima, while Madhyamavyayoga (The Middle One) set around Bhima and his son, Ghatotkacha. The first important play of 20th century was Andha Yug (The Blind Epoch), by Dharamvir Bharati, which came in 1955, found in Mahabharat, both an ideal source and expression of modern predicaments and discontent. Starting with Ebrahim Alkazi, it was staged by numerous directors. V. S. Khandekar's Marathi novel, Yayati (1960), and Girish Karnad's debut play Yayati (1961) are based on the story of King Yayati found in the Mahabharat.[90] Bengali writer and playwright, Buddhadeva Bose wrote three plays set in Mahabharat, Anamni Angana, Pratham Partha and Kalsandhya.[91] Pratibha Ray wrote an award winning novel entitled Yajnaseni from Draupadi's perspective in 1984. Later, Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni wrote a similar novel entitled The Palace of Illusions: A Novel in 2008. Gujarati poet Chinu Modi has written long narrative poetry Bahuk based on the figure Bahuka.[92] Krishna Udayasankar, a Singapore-based Indian author, has written several novels which are modern-day retellings of the epic, most notably the Aryavarta Chronicles Series. Suman Pokhrel wrote a solo play based on Ray's novel by personalizing and taking Draupadi alone in the scene.

Amar Chitra Katha published a 1,260-page comic book version of the Mahabharata.[93]

In film and television

In Indian cinema, several film versions of the epic have been made, dating back to 1920. The Mahābhārata was also reinterpreted by Shyam Benegal in Kalyug.[94] Prakash Jha directed 2010 film Raajneeti was partially inspired by the Mahabharata.[95] A 2013 animated adaptation holds the record for India's most expensive animated film.[96]

In 1988, B. R. Chopra created a television series named Mahabharat. It was directed by Ravi Chopra,[97] and was televised on India's national television (Doordarshan). The same year as Mahabharat was being shown on Doordarshan, that same company's other television show, Bharat Ek Khoj, also directed by Shyam Benegal, showed a 2-episode abbreviation of the Mahabharata, drawing from various interpretations of the work, be they sung, danced, or staged. In the Western world, a well-known presentation of the epic is Peter Brook's nine-hour play, which premiered in Avignon in 1985, and its five-hour movie version The Mahābhārata.[98] In the late 2013 Mahabharat was televised on STAR Plus. It was produced by Swastik Productions Pvt.

A Zee TV television series aired from 26 October 2001 to 26 July 2002 and starred Siraj Mustafa Khan as Krishna and Suneel Mattoo as Yudhishthira.[99][100][101]

Uncompleted projects on the Mahābhārata include one by Rajkumar Santoshi,[102] and a theatrical adaptation planned by Satyajit Ray.[103]

In folk culture

Every year in the Garhwal region of Uttarakhand, villagers perform the Pandav Lila, a ritual re-enactment of episodes from the Mahabharata through dancing, singing, and recitation. The lila is a cultural highlight of the year and is usually performed between November and February. Folk instruments of the region, dhol, damau and two long trumpets bhankore, accompany the action. The amateur actors often break into a spontaneous dance when they are "possessed" by the spirits of the figures of the Mahabharata.[104]

Jain version

Jain versions of Mahābhārata can be found in the various Jain texts like Harivamsapurana (the story of Harivamsa) Trisastisalakapurusa Caritra (Hagiography of 63 Illustrious persons), Pandavacharitra (lives of Pandavas) and Pandavapurana (stories of Pandavas).[105] From the earlier canonical literature, Antakrddaaśāh (8th cannon) and Vrisnidasa (upangagama or secondary canon) contain the stories of Neminatha (22nd Tirthankara), Krishna and Balarama.[106] Prof. Padmanabh Jaini notes that, unlike in the Hindu Puranas, the names Baladeva and Vasudeva are not restricted to Balarama and Krishna in Jain Puranas. Instead, they serve as names of two distinct classes of mighty brothers, who appear nine times in each half of time cycles of the Jain cosmology and rule half the earth as half-chakravartins. Jaini traces the origin of this list of brothers to the Jinacharitra by Bhadrabahu swami (4th–3rd century BCE).[107] According to Jain cosmology Balarama, Krishna and Jarasandha are the ninth and the last set of Baladeva, Vasudeva, and Prativasudeva.[108] The main battle is not the Mahabharata, but the fight between Krishna and Jarasandha (who is killed by Krishna as Prativasudevas are killed by Vasudevas). Ultimately, the Pandavas and Balarama take renunciation as Jain monks and are reborn in heavens, while on the other hand Krishna and Jarasandha are reborn in hell.[109] In keeping with the law of karma, Krishna is reborn in hell for his exploits (sexual and violent) while Jarasandha for his evil ways. Prof. Jaini admits a possibility that perhaps because of his popularity, the Jain authors were keen to rehabilitate Krishna. The Jain texts predict that after his karmic term in the hell is over sometime during the next half time-cycle, Krishna will be reborn as a Jain Tirthankara and attain liberation.[108] Krishna and Balrama are shown as contemporaries and cousins of 22nd Tirthankara, Neminatha.[110] According to this story, Krishna arranged young Neminath's marriage with Rajemati, the daughter of Ugrasena, but Neminatha, empathizing with the animals which were to be slaughtered for the marriage feast, left the procession suddenly and renounced the world.[111][112]

Kuru family tree

This shows the line of royal and family succession, not necessarily the parentage. See the notes below for detail.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Key to Symbols

Notes

- a: Shantanu was a king of the Kuru dynasty or kingdom, and was some generations removed from any ancestor called Kuru. His marriage to Ganga preceded his marriage to Satyavati.

- b: Pandu and Dhritarashtra were fathered by Vyasa in the niyoga tradition after Vichitravirya's death. Dhritarashtra, Pandu and Vidura were the sons of Vyasa with Ambika, Ambalika and a maid servant respectively.

- c: Karna was born to Kunti through her invocation of Surya, before her marriage to Pandu.

- d: Yudhishthira, Bhima, Arjuna, Nakula and Sahadeva were acknowledged sons of Pandu but were begotten by the invocation by Kunti and Madri of various deities. They all married Draupadi (not shown in tree).

- e: Duryodhana and his siblings were born at the same time, and they were of the same generation as their Pandava cousins.

- f : Although the succession after the Pandavas was through the descendants of Arjuna and Subhadra, it was Yudhishthira and Draupadi who occupied the throne of Hastinapura after the great battle.

The birth order of siblings is correctly shown in the family tree (from left to right), except for Vyasa and Bhishma whose birth order is not described, and Vichitravirya and Chitrangada who were born after them. The fact that Ambika and Ambalika are sisters is not shown in the family tree. The birth of Duryodhana took place after the birth of Karna, Yudhishthira and Bhima, but before the birth of the remaining Pandava brothers.

Some siblings of the characters shown here have been left out for clarity; this includes Vidura, half-brother to Dhritarashtra and Pandu.

Cultural influence

In the Bhagavad Gita, Krishna explains to Arjuna his duties as a warrior and prince and elaborates on different Yogic[113] and Vedantic philosophies, with examples and analogies. This has led to the Gita often being described as a concise guide to Hindu philosophy and a practical, self-contained guide to life.[114] In more modern times, Swami Vivekananda, Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose, Bal Gangadhar Tilak, Mahatma Gandhi and many others used the text to help inspire the Indian independence movement.[115][116]

It has also inspired several works of modern Hindi literature, such as Ramdhari Singh Dinkar's Rashmirathi, which is a rendition of Mahabharata centered around Karna and his conflicts. It was written in 1952, and won the prestigious Jnanpith Award in 1972.

Explanatory notes

- ^ Sadwalekar has two translations in Hindi. To read BORI CE in Hindi specifically, go for the translations he published starting from 1968(BORI was published in 1966).

- ^ For example, Draupadi is only wed to Yudhishthira, not to all the Pandava brothers; this might demonstrate ancient Javanese opposition to polyandry. [citation needed] The author later added some female characters to be wed to the Pandavas, for example, Arjuna is described as having many wives and consorts next to Subhadra. Another difference is that Shikhandini does not change her sex and remains a woman, to be wed to Arjuna, and takes the role of a warrior princess during the war. [citation needed] Another twist is that Gandhari is described as an antagonistic character who hates the Pandavas: her hate is out of jealousy because, during Gandhari's swayamvara, she was in love with Pandu but was later wed to his blind elder brother instead, whom she did not love, so she blindfolded herself as a protest.[citation needed]

Citations

- ^ "Mahabharata". The Chambers Dictionary (9th ed.). Chambers. 2003. ISBN 0-550-10105-5.

- ^ "Mahabharata". Collins English Dictionary (13th ed.). HarperCollins. 2018. ISBN 978-0-008-28437-4.

- ^ "Mahabharata". Oxford Dictionaries Online.

- ^ "Mahabharata" Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- ^ Datta, Amaresh (1 January 2006). The Encyclopaedia of Indian Literature (Volume Two) (Devraj to Jyoti). Sahitya Akademi. ISBN 978-81-260-1194-0.

- ^ Austin, Christopher R. (2019). Pradyumna: Lover, Magician, and Son of the Avatara. Oxford University Press. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-19-005411-3. Archived from the original on 7 September 2023. Retrieved 11 January 2020.

- ^ a b c Brockington (1998, p. 26)

- ^ Pattanaik, Devdutt (13 December 2018). "How did the 'Ramayana' and 'Mahabharata' come to be (and what has 'dharma' got to do with it)?". Scroll.in. Archived from the original on 14 August 2020. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ^ Van Buitenen; The Mahabharata – 1; The Book of the Beginning. Introduction (Authorship and Date)

- ^ Stuart, Tristram; Albinia, Alice (16 August 2007). "India's epic struggle". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 6 August 2023. Retrieved 6 August 2023.

- ^ "Mahabharata". 16 May 2021. Archived from the original on 6 August 2023. Retrieved 6 August 2023.

- ^ a b James G. Lochtefeld (2002). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism: A-M. The Rosen Publishing Group. p. 399. ISBN 978-0-8239-3179-8. Archived from the original on 7 September 2023. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- ^ T. R. S. Sharma; June Gaur; Sahitya Akademi (New Delhi, Inde). (2000). Ancient Indian Literature: An Anthology. Sahitya Akademi. p. 137. ISBN 978-81-260-0794-3. Archived from the original on 7 September 2023. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- ^ Spodek, Howard. Richard Mason. The World's History. Pearson Education: 2006, New Jersey. 224, 0-13-177318-6

- ^ Amartya Sen, The Argumentative Indian. Writings on Indian Culture, History and Identity, London: Penguin Books, 2005.

- ^ Fitzgerald, James (1985). "India's Fifth Veda: The Mahabharata's Presentation of Itself". Journal of South Asian Literature. 20 (1): 125–140.

- ^ Mahābhārata, Vol. 1, Part 2. Critical edition, p. 884.

- ^ Davis, Richard H. (2014). The "Bhagavad Gita": A Biography. Princeton University Press. p. 38. ISBN 978-1-4008-5197-3.

- ^ Krishnan, Bal (1978). Kurukshetra: Political and Cultural History. B.R. Publishing Corporation. p. 50. ISBN 9788170180333. Archived from the original on 7 September 2023. Retrieved 6 November 2020.

- ^ Hermann Oldenberg, Das Mahabharata: seine Entstehung, sein Inhalt, seine Form, Göttingen, 1922, [page needed]

- ^ "The Mahabharata" Archived 6 November 2006 at the Wayback Machine at The Sampradaya Sun

- ^ A History of Indian Literature Archived 6 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine, Volume 1 by Maurice Winternitz

- ^ a b c Buitenen (1973) pp. xxiv–xxv

- ^ Sharma, Ruchika (16 January 2017). "The Mahabharata: How an oral narrative of the bards became a text of the Brahmins". Scroll.in. Archived from the original on 17 January 2017. Retrieved 16 January 2017.

- ^ Sukthankar (1933) "Prolegomena" p. lxxxvi. Emphasis is original.

- ^ Gupta & Ramachandran (1976), citing Mahabharata, Critical Edition, I, 56, 33

- ^ SP Gupta and KS Ramachandran (1976), p.3-4, citing Vaidya (1967), p.11

- ^ Brockington, J. L. (1998). The Sanskrit epics, Part 2. Vol. 12. BRILL. p. 21. ISBN 978-90-04-10260-6. Archived from the original on 7 September 2023. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ^ 18 books, 18 chapters of the Bhagavadgita and the Narayaniya each, corresponding to the 18 days of the battle and the 18 armies (Mbh. 5.152.23)

- ^ The Spitzer Manuscript (Beitrage zur Kultur- und Geistesgeschichte Asiens), Austrian Academy of Sciences, 2004. It is one of the oldest Sanskrit manuscripts found on the Silk Road and part of the estate of Dr. Moritz Spitzer.

- ^ Schlingloff, Dieter (1969). "The Oldest Extant Parvan-List of the Mahābhārata". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 89 (2): 334–338. doi:10.2307/596517. JSTOR 596517.

- ^ "Vyasa, can you hear us now?". The Indian Express. 21 November 2015. Archived from the original on 7 June 2020. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ^ J.A.B. van Buitenen, Mahābhārata, Volume 1, p.445, citing W. Caland, The Pañcaviṃśa Brāhmaṇa, p.640-2

- ^ Moriz Winternitz (1996). A History of Indian Literature, Volume 1. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 291–292. ISBN 978-81-208-0264-3. Archived from the original on 6 July 2023. Retrieved 22 November 2018.

- ^ Jean Philippe Vogel (1995). Indian Serpent-lore: Or, The Nāgas in Hindu Legend and Art. Asian Educational Services. pp. 53–54. ISBN 978-81-206-1071-2. Archived from the original on 6 July 2023. Retrieved 22 November 2018.

- ^ mahān vrīhyaparāhṇagṛṣṭīṣvāsajābālabhārabhāratahailihilarauravapravṛddheṣu, 'Pāṇini Research Tool', Sanskrit Dictionary Archived 30 September 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Bronkhorst, J. (2016): How the Brahmins Won. From Alexander to the Guptas, Brill, p. 78-80, 97

- ^ Dio Chrysostom, 53.6-7, trans. H. Lamar Crosby, Loeb Classical Library, 1946, vol. 4, p. 363.

- ^ Christian Lassen, in his Indische Alterthumskunde, supposed that the reference is ultimate to Dhritarashtra's sorrows, the laments of Gandhari and Draupadi, and the valor of Arjuna and Suyodhana or Karna (cited approvingly in Max Duncker, The History of Antiquity (trans. Evelyn Abbott, London 1880), vol. 4, p. 81). This interpretation is endorsed in such standard references as Albrecht Weber's History of Indian Literature but has sometimes been repeated as fact instead of as interpretation.

- ^ a b Ghadyalpatil, Abhiram (10 October 2016). "Maharashtra builds up a case for providing quotas to Marathas". Livemint. Archived from the original on 7 June 2020. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ^ SECTION XXVI (Go-harana Parva) Archived 30 November 2021 at the Wayback Machine sacred-texts.com.

- ^ "The Mahabharata, Book 6: Bhishma Parva: Bhagavat-Gita Parva: Section XXV (Bhagavad Gita Chapter I)". Sacred-texts.com. Archived from the original on 21 May 2012. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- ^ "The Mahabharata, Book 6: Bhishma Parva: Bhagavat-Gita Parva: Section XLII (Bhagavad Gita, Chapter XVIII)". Sacred-texts.com. Archived from the original on 21 May 2012. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- ^ The Ashvamedhika-parva is also preserved in a separate version, the Jaimini-Bharata (Jaiminiya-Ashvamedha) where the frame dialogue is replaced, the narration being attributed to Jaimini, another disciple of Vyasa. . It describes how Arjuna alone conquered the whole earth once again. This version contains far more devotional material (related to Krishna) than the standard epic and probably dates to the 12th century. It has some regional versions, the most popular being the Kannada one by Devapurada Annama Lakshmisha (16th century).The Mahabharata Archived 6 November 2006 at the Wayback Machine[citation needed]

- ^ In discussing the dating question, historian A. L. Basham says: "According to the most popular later tradition the Mahabharata War took place in 3102 BCE, which in the light of all evidence, is quite impossible. More reasonable is another tradition, placing it in the 15th century BCE, but this is also several centuries too early in the light of our archaeological knowledge. Probably the war took place around the beginning of the 9th century BCE; such a date seems to fit well with the scanty archaeological remains of the period, and there is some evidence in the Brahmana literature itself to show that it cannot have been much earlier." Basham, p. 40, citing HC Raychaudhuri, Political History of Ancient India, pp.27ff.

- ^ M Witzel, Early Sanskritization: Origin and Development of the Kuru state, EJVS vol.1 no.4 (1995); also in B. Kölver (ed.), Recht, Staat und Verwaltung im klassischen Indien. The state, the Law, and Administration in Classical India, München, R. Oldenbourg, 1997, p.27-52

- ^ A.D. Pusalker, History and Culture of the Indian People, Vol I, Chapter XIV, p.273

- ^ FE Pargiter, Ancient Indian Historical Tradition, p.180. He shows estimates of the average as 47, 50, 31, and 35 for various versions of the lists.

- ^ Pargiter, op.cit. p.180-182

- ^ B. B. Lal, Mahabharata and Archaeology in Gupta and Ramachandran (1976), p.57-58

- ^ Keay, John (2000). India: A History. New York City: Grove Press. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-8021-3797-5. Archived from the original on 3 July 2023. Retrieved 22 September 2024.

- ^ Gupta and Ramachandran (1976), p.246, who summarize as follows: "Astronomical calculations favor 15th century BCE as the date of the war while the Puranic data place it in the 10th/9th century BCE. Archaeological evidence points towards the latter." (p.254)

- ^ "Lord Krishna lived for 125 years | India News – Times of India". The Times of India. 8 September 2004. Archived from the original on 23 October 2020. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ^ "5151 years of Gita". 19 January 2014. Archived from the original on 8 November 2017. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ^ Gupta and Ramachandran (1976), p.55; AD Pusalker, HCIP, Vol I, p.272

- ^ AD Pusalker, op.cit. p.272

- ^ A.M. Shastri (1991). Varāhamihira and His Times. Kusumanjali. pp. 31–33, 37. OCLC 28644897. Archived from the original on 3 July 2023. Retrieved 22 March 2023.

- ^ "Sanskrit, Tamil and Pahlavi Dictionaries" (in German). Webapps.uni-koeln.de. 11 February 2003. Archived from the original on 26 January 2008. Retrieved 9 February 2008.

- ^ Mani, Vettam (1975). Puranic Encyclopaedia: A Comprehensive Dictionary With Special Reference to the Epic and Puranic Literature. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. p. 263. ISBN 978-0-8426-0822-0.

- ^ "Book 1: Adi Parva: Jatugriha Parva". Sacred-texts.com. Archived from the original on 25 March 2010. Retrieved 1 September 2010.

- ^ VISHNU S. SUKTHANKAR (11 March 2018). "THE MAHABHARATHA". BHANDARKAR ORIENTAL RESEARCH INSTITUTE, POONA – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "The Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute : Mahabharata Project". bori.ac.in. Archived from the original on 20 December 2017. Retrieved 3 November 2019.

- ^ M. A. Mehendale (1 January 2001). "Interpolations in the Mahabharata" – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "Book 2: Sabha Parva: Sabhakriya Parva". Sacred-texts.com. Archived from the original on 27 May 2010. Retrieved 1 September 2010.

- ^ "Sabha parva". Sacred-texts.com. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- ^ Nath Soni, Lok (2000). The Cattle and the Stick An Ethnographic Profile of the Raut of Chhattisgarh. Anthropological Survey of India. p. 16. ISBN 9788185579573.

- ^ Shome, Alo (2000). Krishna Charitra: The Essence of Bankim Chandra. Pustak Mahal. p. 104. ISBN 8122310354.

- ^ Rajagopalachari, Chakravarti (2005). "Yudhishthira's final trial". Mahabharata (45th ed.). Mumbai: Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan. ISBN 978-81-7276-368-8.

- ^ Robinson, P.F. (2003). Just War in Comparative Perspective. Ashgate. p. 117. ISBN 978-0-7546-3587-1. Retrieved 2 October 2015.

- ^ "picture details". Plant Cultures. Archived from the original on 13 November 2007. Retrieved 1 September 2010.

- ^ Mohanta, Sambaru Chandra (2012). "Mahabharata". In Sirajul Islam; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza; Ahmed, Sabbir (eds.). Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. OL 30677644M. Retrieved 22 November 2024.

- ^ Husam, Shamshad. "বাংলা সাহিত্যে সিলেট". Thikana (in Bengali). Archived from the original on 26 October 2022. Retrieved 31 October 2022.

- ^ Gaṅgā Rām, Garg (1992). Encyclopaedia of the Hindu world, Volume 1. Concept Publishing Company. p. 129. ISBN 978-81-7022-376-4.

- ^ Several editions of the Kisari Mohan Ganguli translation of the Mahabharata incorrectly cite the publisher, Pratap Chandra Roy, as the translator and this error has been propagated into secondary citations. See the publisher's preface to the current Munshiram Manoharlal edition for an explanation.

- ^ The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa translated by Kisari Mohan Ganguli Archived 11 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine at the Internet Sacred Text Archive

- ^ P. Lal. "Kisari Mohan Ganguli and Pratap Chandra Roy". An Annotated Mahabharata Bibliography. Calcutta. Archived from the original on 5 June 2014. Retrieved 9 September 2013.

- ^ The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa translated by Romesh Chunder Dutt Archived 10 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine at the Online Library of Liberty.

- ^ a b "Review : Bibek DebRoy: The Mahabharata, volume 7". pradipbhattacharya.com. Archived from the original on 2 June 2021. Retrieved 31 May 2021.

- ^ a b Agarwal, Abhinav (12 April 2015). "Book review: 'The Mahabharata' Volume 10 translated by Bibek Debroy". DNA India. Archived from the original on 2 June 2021. Retrieved 31 May 2021.

- ^ "Indian Artwork – Buddha Statues & Hindu Books – Exotic India Art". www.exoticindiaart.com. Archived from the original on 7 September 2023. Retrieved 27 June 2021.

- ^ S R, Ramaswamy (1972). ಮಹಾಭಾರತದ ಬೆಳವಣಿಗೆ. Mysore: Kavyalaya Publishers.

- ^ Veda Vyasa, S. D. Satwalekar. Mahabharata with Hindi Translation – SD Satwalekar (in Sanskrit). Sanskrit eBooks.

- ^ Chikermane, Gautam (20 July 2012). "Review: The Mahabharata: Volume 5". Hindustan Times. Archived from the original on 2 June 2021. Retrieved 31 May 2021.

- ^ Fitzgerald, James (2009). "Reading Suggestions for Getting Started". Brown. Archived from the original on 4 February 2021.

- ^ "Frederick M. Smith". University of Iowa. Archived from the original on 24 October 2021. Retrieved 12 October 2021.

- ^ Bhandarkar Institute, Pune Archived 19 October 2018 at the Wayback Machine—Virtual Pune

- ^ Srinivas, Smriti (2004) [2001]. Landscapes of Urban Memory. Orient Longman. p. 23. ISBN 978-81-250-2254-1. OCLC 46353272.

- ^ Bellwood, Peter; Fox, James J.; Tryon, Darrell, eds. (2006). The Javanization of the Mahābhārata, Chapter 15. Indic Transformation: The Sanskritization of Jawa and the Javanization of the Bharata. ANU Press. doi:10.22459/A.09.2006. ISBN 9780731521326. Archived from the original on 11 November 2014. Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ^ "Indonesian Ramayana: The Uttarakanda by Dr. I Gusti Putu Phalgunadi: Sundeep Prakashan, New Delhi 9788175740532 Hardcover, First edition". abebooks.com. Archived from the original on 4 August 2020. Retrieved 27 November 2018.

- ^ Don Rubin (1998). The World Encyclopedia of Contemporary Theatre: Asia. Taylor & Francis. p. 195. ISBN 978-0-415-05933-6. Archived from the original on 7 September 2023. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ^ The Mahabharata as Theatre Archived 14 January 2010 at the Wayback Machine by Pradip Bhattacharya, 13 June 2004.

- ^ Topiwala, Chandrakant (1990). "Bahuk". Gujarati Sahityakosh (Encyclopedia of Gujarati Literature) (in Gujarati). Vol. 2. Ahmedabad: Gujarati Sahitya Parishad. p. 394.

- ^ Pai, Anant (1998). Pai, Anant (ed.). Amar Chitra Katha Mahabharata. Kadam, Dilip (illus.). Mumbai: Amar Chitra Katha. p. 1200. ISBN 978-81-905990-4-7.

- ^ "What makes Shyam special". Hinduonnet.com. 17 January 2003. Archived from the original on 12 January 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Kumar, Anuj (27 May 2010). "Fact of the matter". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 30 March 2014. Retrieved 11 August 2013.

- ^ "Mahabharat: Theatrical Trailer (Animated Film)". 19 November 2013. Archived from the original on 17 December 2013. Retrieved 16 December 2013.

- ^ Mahabharat at IMDb (1988–1990 TV series)

- ^ The Mahabharata at IMDb (1989 mini-series).

- ^ "Zee TV to launch two mythological serials". Exchange4Media Dot Com. 25 December 2001. Retrieved 24 June 2022.

- ^ "Good Lord!". Tribune India Dot Com. 13 January 2002. Retrieved 2 July 2022.

- ^ "Sanjay Khan excited about Maha Kavya Mahabharat". Times Of India Dot Com. 21 October 2001. Retrieved 2 July 2022.

- ^ "In brief: Mahabharat will be most expensive Indian movie ever". The Guardian. 24 February 2003. Archived from the original on 26 March 2017. Retrieved 12 December 2016 – via www.theguardian.com.

- ^ C. J. Wallia (1996). "IndiaStar book review: Satyajit Ray by Surabhi Banerjee". Archived from the original on 14 May 2008. Retrieved 31 May 2009.

- ^ Sax, William Sturman (2002). Dancing the Self: Personhood and Performance in the Pāṇḍava Līlā of Garhwal. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195139150.

- ^ Jaini, Padmanabh (2000). Collected Papers on Jaina Studies. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publ. ISBN 978-81-208-1691-6. p. 351-52

- ^ Shah, Natubhai (1998). Jainism: The World of Conquerors. Volume I and II. Sussex: Sussex Academy Press. ISBN 978-1-898723-30-1. vol 1 pp. 14–15

- ^ Jaini, Padmanabh (2000). Collected Papers on Jaina Studies. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publ. ISBN 978-81-208-1691-6. p. 377

- ^ a b Jaini, Padmanabh (1998). The Jaina Path of Purification. New Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-1578-0. p.305

- ^ Jaini, Padmanabh (2000). Collected Papers on Jaina Studies. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publ. ISBN 978-81-208-1691-6. p. 351

- ^ Roy, Ashim Kumar (1984). A history of the Jainas. New Delhi: Gitanjali Pub. House. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-8364-1136-2. OCLC 11604851.

- ^ Helen, Johnson (2009) [1931]. Muni Samvegayashvijay Maharaj (ed.). Trisastiśalākāpurusacaritra of Hemacandra: The Jain Saga. Vol. Part II. Baroda: Oriental Institute. ISBN 978-81-908157-0-3. refer story of Neminatha

- ^ Devdutt Pattanaik (2 March 2017). "How different are the Jain Ramayana and Jain Mahabharata from Hindu narrations?". Devdutt. Archived from the original on 7 March 2017. Retrieved 22 March 2017.

- ^ "Introduction to the Bhagavad Gita". Yoga.about.com. Archived from the original on 3 December 2010. Retrieved 1 September 2010.

- ^ Maharishi Mahesh Yogi; On the Bhagavad Gita: A New Translation and Commentary with Sanskrit Text, chapters 1 to 6, Preface p. 9

- ^ Stevenson, Robert W., "Tilak and the Bhagavadgita's Doctrine of Karmayoga", in Minor, p. 44.

- ^ Jordens, J. T. F., "Gandhi and the Bhagavadgita", in Minor, p. 88.

General sources

- Badrinath, Chaturvedi. The Mahābhārata: An Inquiry in the Human Condition, New Delhi, Orient Longman (2006).

- Bandyopadhyaya, Jayantanuja (2008). Class and Religion in Ancient India. Anthem Press.

- Basham, A. L. (1954). The Wonder That Was India: A Survey of the Culture of the Indian Sub-Continent Before The Coming of the Muslims. New York: Grove Press.

- Bhasin, R. V. Mahabharata published by National Publications, India, 2007.

- J. Brockington. The Sanskrit Epics, Leiden (1998).

- Buitenen, Johannes Adrianus Bernardus (1978). The Mahābhārata. 3 volumes (translation / publication incomplete due to his death). University of Chicago Press.

- Chaitanya, Krishna (K.K. Nair). The Mahabharata, A Literary Study, Clarion Books, New Delhi 1985.

- Gupta, S. P. and Ramachandran, K. S. (ed.). Mahabharata: myth and reality. Agam Prakashan, New Delhi 1976.

- Hiltebeitel, Alf. The Ritual of Battle, Krishna in the Mahabharata, SUNY Press, New York 1990.

- Hopkins, E. W. The Great Epic of India, New York (1901).

- Jyotirmayananda, Swami. Mysticism of the Mahabharata, Yoga Research Foundation, Miami 1993.

- Katz, Ruth Cecily Arjuna in the Mahabharata, University of South Carolina Press, Columbia 1989.

- Keay, John (2000). India: A History. Grove Press. ISBN 978-0-8021-3797-5.

- Majumdar, R. C. (1951). The History and Culture of the Indian People: (Volume 1) The Vedic Age. London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd.

- Lerner, Paule. Astrological Key in Mahabharata, David White (trans.) Motilal Banarsidass, New Delhi 1988.

- Mallory, J. P (2005). In Search of the Indo-Europeans. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-27616-1

- Mehta, M. The problem of the double introduction to the Mahabharata, JAOS 93 (1973), 547–550.

- Minkowski, C. Z. Janamehayas Sattra and Ritual Structure, JAOS 109 (1989), 410–420.

- Minkowski, C. Z. 'Snakes, Sattras and the Mahabharata', in: Essays on the Mahabharata, ed. A. Sharma, Leiden (1991), 384–400.

- Oldenberg, Hermann. Zur Geschichte der Altindischen Prosa, Berlin (1917)

- Oberlies, Th. 'The Counsels of the Seer Narada: Ritual on and under the surface of the Mahabharata', in: New methods in the research of epic (ed. H. L. C. Tristram), Freiburg (1998).

- Oldenberg, H. Das Mahabharata, Göttingen (1922).

- Pāṇini. Ashtādhyāyī. Book 4. Translated by Chandra Vasu. Benares, 1896. (in Sanskrit and English)

- Pargiter, F. E. Ancient Indian Historical Tradition, London 1922. Repr. Motilal Banarsidass 1997.

- Sattar, Arshia (transl.) (1996). The Rāmāyaṇa by Vālmīki. Viking. p. 696. ISBN 978-0-14-029866-6.

- Sukthankar, Vishnu S. and Shrimant Balasaheb Pant Pratinidhi (1933). The Mahabharata: for the first time critically edited. Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute.

- Sullivan, Bruce M. Seer of the Fifth Veda, Krsna Dvaipayana Vyasa in the Mahabharata, Motilal Banarsidass, New Delhi 1999.

- Sutton, Nicholas. Religious Doctrines in the Mahabharata, Motilal Banarsidass, New Delhi 2000.

- Utgikar, N. B. "The mention of the Mahābhārata in the Ashvalayana Grhya Sutra", Proceedings and Transactions of the All-India Oriental Conference, Poona (1919), vol. 2, Poona (1922), 46–61.

- Vaidya, R. V. A Study of Mahabharat; A Research, Poona, A.V.G. Prakashan, 1967

- Witzel, Michael, Epics, Khilas and Puranas: Continuities and Ruptures, Proceedings of the Third Dubrovnik International Conference on the Sanskrit Epics and Puranas, ed. P. Koskiallio, Zagreb (2005), 21–80.

External links

- Sacred-Texts: Hinduism – English translation of 18 parvas of Mahabharata

- harivamsham – mahaabhaarat khila parva – English translation of harivamsa Parva of Mahabharata

- Sanskrit etext of the Mahābhārata online (licensed and approved by BORI)

- All volumes in 12 PDF files (Holybooks.com, 181 MB in total)

- Reading Suggestions, J. L. Fitzgerald, Das Professor of Sanskrit, Department of Classics, Brown University

- Critical Edition Prepared by Scholars at Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute BORI

The Mahabharata by Vyasa: The epic of ancient India condensed into English verse public domain audiobook at LibriVox

The Mahabharata by Vyasa: The epic of ancient India condensed into English verse public domain audiobook at LibriVox