The Notorious Byrd Brothers

| The Notorious Byrd Brothers | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | January 15, 1968[nb 1] | |||

| Recorded | June 21 – December 6, 1967 | |||

| Studio | Columbia, Hollywood | |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 28:28 | |||

| Label | Columbia | |||

| Producer | Gary Usher | |||

| The Byrds chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from The Notorious Byrd Brothers | ||||

| ||||

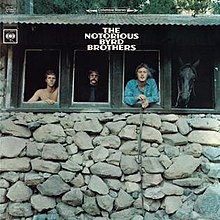

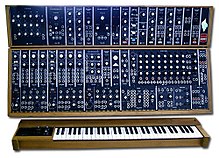

The Notorious Byrd Brothers is the fifth album by the American rock band the Byrds, released on January 15, 1968, by Columbia Records.[1][2] The album represents the pinnacle of the Byrds' late-'60s musical experimentation, with the band blending together elements of psychedelia, folk rock, country, electronic music, baroque pop, and jazz.[3][4][5] With producer Gary Usher, they made extensive use of a number of studio effects and production techniques, including phasing, flanging, and spatial panning.[6][7][8] The Byrds also introduced the sound of the pedal steel guitar and the Moog modular synthesizer into their music, making it one of the first LP releases on which the Moog appears.[7][9]

Recording sessions for The Notorious Byrd Brothers took place throughout the latter half of 1967 and were fraught with tension, resulting in the loss of two members of the band;[9] rhythm guitarist David Crosby was fired in October 1967 and drummer Michael Clarke left the sessions midway through recording, returning briefly before finally being dismissed after completion of the album.[10][11] Additionally, original band member Gene Clark, who had left the group in early 1966, rejoined for three weeks during the making of the album, before leaving again.[12] Author Ric Menck has commented that in spite of these changes in personnel and the conflict surrounding its creation, The Notorious Byrd Brothers is the band's most cohesive and ethereal-sounding album statement.[13]

The Notorious Byrd Brothers reached number 47 on the Billboard Top LPs chart and number 12 on the UK Album Chart.[14][15] A cover of the Gerry Goffin and Carole King song "Goin' Back" was released in October 1967 as the lead single from the album to mild chart success.[7] Although The Notorious Byrd Brothers was critically praised at the time of its release, it was only moderately successful commercially, particularly in the United States.[16] The album later came to be widely regarded as one of the Byrds' best album releases, as well as their most experimental and progressive.[5][6][13] Byrds expert Tim Connors has described the album's title as evoking a gang of outlaws from the American Old West.[4]

Background

[edit]The recording of The Notorious Byrd Brothers, during the latter half of 1967, was marked by severe internal dissolution and acrimony.[4] The Byrds began the recording sessions as a four-piece band, consisting of Roger McGuinn, David Crosby, Chris Hillman, and Michael Clarke—the same line-up that had recorded their two previous albums.[17] By the time of the album's release, however, only McGuinn and Hillman remained in the group.[5] The first line-up change occurred when drummer Michael Clarke quit the sessions after having played on several songs, over disputes with Crosby and the other band members over his playing ability and his apparent dissatisfaction with the material the three songwriting members of the band were providing.[18][19] Though he remained a band member and continued to honor his live concert commitments with the group, Clarke was temporarily replaced in the studio by noted session drummers Jim Gordon and Hal Blaine.[18][19]

David Crosby was then fired by McGuinn and Hillman and replaced by a former member of the Byrds, Gene Clark, who stayed on board for just three weeks before leaving again.[10][12] Prior to finishing the album, Michael Clarke also returned from his self-imposed exile to co-write and play on the track "Artificial Energy", only to be informed by McGuinn and Hillman that he was an ex-Byrd after the album was completed.[11] Amid so many changes in band personnel, McGuinn and Hillman needed to rely upon outside musicians to complete the album.[11] Among these hired musicians was Clarence White, who had also played on the group's previous album, Younger Than Yesterday.[4] His contributions to these and the Byrds' Sweetheart of the Rodeo album, along with his friendship with Hillman, eventually led to his being hired as a full-time member of the band in 1968.[20]

David Crosby's dismissal

[edit]

David Crosby was fired by McGuinn and Hillman in October 1967, partly as a result of friction arising from Crosby's displeasure at the band's wish to record the Goffin–King composition "Goin' Back".[10] Crosby felt that recording the song was a step backwards artistically, especially when the band contained three active songwriters.[13] Another factor that contributed to Crosby's dismissal was his controversial song "Triad", a risqué composition about a ménage à trois that was in direct competition with "Goin' Back" for a place on the album.[5] He later gave the tune to Jefferson Airplane, who included a version of the song on their 1968 album Crown of Creation.[19][21] Although the Byrds did record "Triad", the song's subject matter compelled McGuinn and Hillman to prevent it from being released at the time.[10] The track was first issued on the band's 1987 archival compilation album, Never Before, and was later added to The Notorious Byrd Brothers as a bonus track on the 1997 Columbia/Legacy reissue.[22][23]

Crosby had also annoyed the other members of the Byrds during their performance at the Monterey Pop Festival when he gave lengthy in-between-song speeches on several controversial subjects, including the JFK assassination and the benefits of giving LSD to "all the statesmen and politicians in the world".[24] He further irritated his bandmates at Monterey by performing with rival group Buffalo Springfield, filling in for ex-member Neil Young.[25]

His stock within the band deteriorated still further following the commercial failure of his song "Lady Friend", when it was released as the A-side of a Byrds single in July 1967.[26] His absence from many of the recording sessions for The Notorious Byrd Brothers was the final straw for McGuinn and Hillman. Crosby received a generous severance package and began to collaborate with his new musical partner, Stephen Stills.[10] It has been suggested that the horse on the cover of the album was unkindly intended to represent Crosby, although this has been denied by both McGuinn and Hillman.[27]

Much to Crosby's chagrin, McGuinn and Hillman reworked his unfinished song "Draft Morning" following his departure and included it in the final running order for the album, giving themselves a co-writing credit.[3] Crosby ended up playing on around half of The Notorious Byrd Brothers: on his own three songs, along with "Change Is Now" and "Old John Robertson".[16] He also appears on several bonus tracks on the 1997 reissue, including "Triad", "Universal Mind Decoder" and an early version of "Goin' Back".[28]

Gene Clark's temporary return

[edit]Following Crosby's departure, Gene Clark was asked to rejoin the band.[13] Clark had originally left the Byrds in early 1966 due to his fear of flying and his tendency towards anxiety and paranoia.[29] His debut solo album (co-produced by the Byrds' then current producer, Gary Usher, with both Clarke and Hillman playing on it) had been a critical success, but a commercial failure and Clark was currently inactive.[30] Clark rejoined the Byrds in October 1967 for three weeks, during which time he and the band performed on The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour television program, lip-syncing "Goin' Back" and "Mr. Spaceman".[12] The Byrds also played several live dates with Clark during a tour of the Midwest.[12] Following the final concert of the tour, Clark's fear of flying again became a problem when it prevented him from taking a flight to New York with his bandmates and, as a result, he left the band soon after.[12]

It has been debated by biographers and band historians just how involved Clark was in the recording of The Notorious Byrd Brothers.[13] Clark himself claimed during a 1988 interview for radio station KBSG 97 that he was involved in the recording of "Goin' Back" and some other songs from the same period, although he didn't specify what his contributions might have been.[31] There is also studio documentation and eyewitness accounts to suggest that Clark contributed backing vocals to "Goin' Back" and "Space Odyssey".[12][13] One of those eyewitnesses, John Noreen of the L.A. folk rock band the Rose Garden, has stated in an interview that he clearly remembers being at Columbia Recording Studios during sessions for the album and seeing Clark record his backing vocals.[12] This has been corroborated by the Rose Garden's drummer, Bruce Bowdin, who has claimed that Clark's voice can be heard most clearly on the mono mix of "Goin' Back" which was released as a single.[12] Conversely, the Rose Garden's bass player William Fleming, who was also there, recalled that although Clark was in the studio he didn't participate in any recording.[32] Author and musician Ric Menck has remarked that if Clark is present on either "Space Odyssey" or "Goin' Back", his contributions are not obvious and must have been buried very low in the mix by producer Gary Usher.[13]

The Byrds' lead guitarist, Roger McGuinn, cannot remember whether Clark contributed to the album or not, but he has admitted that it is possible.[12] McGuinn has, however, gone on record as stating that he wrote the song "Get to You" with Clark, and that the writing credits on the album are mistaken; they should have read McGuinn/Clark, rather than McGuinn/Hillman.[12] However, in an interview published in the November 2012 edition of Uncut magazine, Hillman stated that he definitely had a hand in writing the song with McGuinn, although he was unsure whether Clark also contributed to it or not.[33]

Music

[edit]Production

[edit]Despite its troubled genesis, the album contains some of the band's most gentle and ethereal music, as well as some of its most progressive and experimental.[13] In a 2002 interview, McGuinn said it was "kind of Beatles-inspired" and cited their album Revolver as an influence.[34] Lyrically, it attempted to deal with many contemporary themes such as peace, ecology, freedom, drug use, alienation and mankind's place in the universe.[3] The album, as a whole, represented the apex of the McGuinn–Crosby–Hillman songwriting partnership, and took the musical experimentation of the original Byrds to its farthest logical extreme, mixing folk rock, country, psychedelia and jazz, often within a single song.[4][5][3] The band and producer Gary Usher also used a number of innovative studio-based production techniques on the album, in particular making heavy use of phasing, spatial panning, and rotary speaker effects.[6][8][35]

The band also began experimenting with the Moog modular synthesizer on a number of tracks, making The Notorious Byrd Brothers one of the first rock albums to feature the instrument.[7] McGuinn had first discovered the Moog during the Monterey Pop Festival, where the instrument's inventor, Robert Moog, had set up a booth to demonstrate his new creation to the musicians who were performing at the festival.[36] Being something of an electronics buff, McGuinn was eager to experiment with the synthesizer in the recording studio, although reportedly, Hillman failed to share his enthusiasm for the instrument.[36] Although McGuinn and Usher played the Moog parts on the song "Space Odyssey" themselves, they ceded the instrument's other appearances on the album to electronic music pioneer and session musician Paul Beaver.[7][36]

The album also featured the pedal steel guitar playing of session musician Red Rhodes, which represented the first use of the instrument on a Byrds' recording.[9][37] This use of pedal steel, along with Clarence White's countrified guitar playing, foreshadowed the country rock direction that the band would explore on their next album, Sweetheart of the Rodeo.[4][38]

The songs

[edit]The album's opening track, "Artificial Energy", features a prominent horn section and, as such, can be seen as a stylistic relative of "Lady Friend" and "So You Want to Be a Rock 'n' Roll Star", two earlier Byrds' songs that made use of brass.[35] The song deals with the dark side of amphetamine use and it was Chris Hillman who initially suggested that the band should "write a song about speed".[4][28] The title was suggested by drummer Michael Clarke, and his input in the creation of the song was sufficient to afford him a rare writing credit.[35] Although the song's lyrics initially seem to be extolling the virtues of amphetamines, the tale turns darker in the final verse when it becomes apparent that the drug taker has been imprisoned for murdering a homosexual man, as evidenced by the song's final couplet: "I'm coming down off amphetamine/And I'm in jail 'cause I killed a queen."[3][39] Although the press had accused the Byrds of writing songs about drugs in the past, specifically with "Eight Miles High" and "5D (Fifth Dimension)", when the band finally did record a song unequivocally dealing with drugs it was largely ignored by journalists.[3]

"Artificial Energy" is followed on the album by the poignant and nostalgic Goffin–King song "Goin' Back".[2] With its chiming 12-string Rickenbacker guitar and polished harmony singing, band biographer Johnny Rogan has described the song as providing a sharp contrast to the negativity and violence of the opening track.[38][3] The song's lyrics describe an attempt on the part of the singer to reject the cynicism that comes with being an adult in favor of the innocence of childhood.[38] Thematically, the song recalled the title of the Byrds' previous album, Younger Than Yesterday, and the understated pedal steel guitar playing of Red Rhodes gives the track a subtle country flavor.[28][40]

A second Goffin–King composition, "Wasn't Born to Follow", also displays country and western influences, albeit filtered through the band's psychedelic and garage rock tendencies.[41] The song's country leanings are underscored by the criss-crossing musical dialogue between the electric guitar and pedal steel.[41] The rural ambiance is further heightened by the striking imagery of the lyrics which outline the need for escape and independence: a subject perfectly in keeping with the hippie ethos of the day.[41][42]

Another song on the album that deals with the need to escape the confines of society is David Crosby's "Dolphin's Smile".[43] The song was an early example of Crosby's penchant for using nautical imagery in his songs, a thematic trait he would utilize in future compositions, including "Wooden Ships" and "The Lee Shore".[28] The theme of unfettered idyllic bliss is further explored in the Hillman-penned "Natural Harmony".[28] Like "Goin' Back", "Natural Harmony" conveys a sense of longing for the innocence of youth, albeit filtered through the awareness-raising properties of psychedelic drugs.[3] It has been suggested by some commentators that the song exhibits the strong influence of Crosby's writing style, with its laid-back, jazzy feel and dreamy, high tenor vocal part.[4][44]

The McGuinn and Hillman composition "Change Is Now", with its lyrics advising the listener to live life to the full, represents a celebration of the philosophy of carpe diem (popularly translated as "seize the day").[3] Within this context, the song's lyrics explored a number of other themes, including epiphenomenalism, communalism, and human ecology.[3] The quasi-philosophical nature of the song prompted McGuinn to flippantly describe it in a 1969 interview as "another one of those guru-spiritual-mystic songs that no-one understood".[3] An early instrumental recording of the song, listed under its original working title of "Universal Mind Decoder", was included as a bonus track on the 1997 reissue of The Notorious Byrd Brothers.[23] "Change Is Now" is notable for being the only song on the album to feature both Crosby and future Byrd Clarence White together on the same track.[28]

"Draft Morning" is a song about the horrors of the Vietnam War, as well as a protest against the conscription of men into the military during the conflict.[2][45] The song was initially written by Crosby, but he was fired from the Byrds shortly after he had introduced it to the rest of the band.[45] However, work had already begun on the song's instrumental backing track by the time of Crosby's departure.[45] Controversially, McGuinn and Hillman decided to continue working on the song, despite its author no longer being a member of the band.[3] Having only heard the song's lyrics in their original incarnation a few times, McGuinn and Hillman couldn't remember all of the words when they came to record the vocals and so decided to rewrite the song with their own lyrical additions, giving themselves a co-writing credit in the process.[4] This angered Crosby considerably, since he felt, with some justification, that McGuinn and Hillman had stolen his song.[45] Despite its troubled evolution, "Draft Morning" is often considered one of Crosby's best songs from his tenure with the Byrds.[4][13] Lyrically, it follows a newly recruited soldier from the morning of his induction into the military through to his experiences of combat and as such, illustrates the predicament faced by many young American men during the 1960s.[4][3] The song also makes extensive use of battlefield sound effects, provided for the band by the Los Angeles comedy troupe the Firesign Theatre.[28]

Another of Crosby's songwriting contributions to the album, "Tribal Gathering", was, for many years, assumed to have been inspired by the Human Be-In: A Gathering Of Tribes, a counter-culture happening held in San Francisco's Golden Gate Park on January 12, 1967.[4][28] However, in the 2000s, Crosby revealed that the song was actually inspired by another hippie gathering held at Elysian Park near Los Angeles on March 26, 1967.[46][47] Played in a jazzy, 5/4 time signature, the song's vocal arrangement was greatly influenced by the music of the Four Freshmen, a vocal group that Crosby had admired as a youngster.[46]

Another song on the album that uses a 5/4 time signature, albeit with occasional shifts into 3/4 time, is "Get to You".[3] The song recounts a plane trip to London, England, just prior to the advent of autumn, but the identity of the enigmatic "you" mentioned in the song's title is not specified in the lyrics and thus, can be interpreted as either a waiting lover or as the city of London itself.[3] Although it has been claimed by McGuinn that Clark co-wrote the song, he had left the Byrds again by the time it was recorded and therefore does not appear on the track.[7]

"Old John Robertson", which had already been issued some six months earlier as the B-side of the "Lady Friend" single, was another country-tinged song that looked forward to the band's future country rock experimentation.[1][2] The song was inspired by a retired film director who lived in the small town near San Diego where Hillman grew up.[28] According to Hillman, John S. Robertson was something of an eccentric figure around the town, regularly wearing a Stetson hat and sporting a white handlebar moustache, which gave him the appearance of a character out of the old American West.[28] In the song, Hillman recalls the children of the town and their cruel laughter at this colorful figure, as well as the combination of awe and fear that he elicited in the townsfolk.[28] During the recording of the song, Crosby switched instruments with Hillman to play bass instead of his usual rhythm guitar.[8] The track also makes liberal use of the studio effects known as phasing and flanging, particularly during the song's orchestral middle section and subsequent verse.[7] The version of "Old John Robertson" found on the B-side of the "Lady Friend" single is a substantially different mix from the version that appears on The Notorious Byrd Brothers album.[4]

The final track on the album, "Space Odyssey", is a musical retelling of Arthur C. Clarke's short story "The Sentinel", which was also the inspiration for Stanley Kubrick's 1968 film, 2001: A Space Odyssey.[28] The song makes extensive use of the Moog modular synthesizer and features a droning, dirge-like melody reminiscent of a sea shanty.[27][36] Since "Space Odyssey" predates the release of 2001: A Space Odyssey, McGuinn and his co-writer, Robert J. Hippard, composed lyrics that referred to a pyramid being found on the Moon, as was the case in "The Sentinel".[48] However, the pyramid was replaced by a rectangular monolith in both the film and the accompanying novelization.[49]

Release and reception

[edit]| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| Encyclopedia of Popular Music | |

| Pitchfork | 9.1/10[51] |

| Rolling Stone | |

The Notorious Byrd Brothers was released on January 15, 1968, in the United States (catalogue item CL 2775 in mono, CS 9575 in stereo) and on April 12, 1968, in the UK (catalogue item 63169 in mono, S 63169 in stereo).[1][16] However, there is some debate about the U.S. release date, with some sources suggesting that it may have been brought forward to January 3, 1968.[2][5] Regardless, the album's appearance during the first month of 1968 surprised many fans of the band, who had been led to believe by contemporary press reports that the album was still in the planning stages.[3]

It peaked at number 47 on the Billboard Top LPs chart, during a chart stay of 19 weeks, but fared better in the United Kingdom where it reached number 12, spending a total of 11 weeks on the UK chart.[14][15] The album's front cover photograph was taken by Guy Webster, who had also been responsible for the cover of the Byrds' Turn! Turn! Turn! album.[16] The "Goin' Back" single was released ahead of the album on October 20, 1967, and reached number 89 on the Billboard Hot 100, but failed to chart in the UK.[7] The album is notable for being the last Byrds LP to be commercially issued in mono in the United States, although subsequent albums continued to be released in both mono and stereo variations overseas.[1]

The album was almost universally well received by the music press upon release, with Jon Landau in the newly launched Rolling Stone magazine noting that "When the Byrds get it together on record they are consistently brilliant."[16][3] Landau went on to praise the Byrds' musical eclecticism, before stating: "Their music is possessed by a never-ending circularity and a rich, child-like quality. It has a timelessness to it, not in the sense that you think their music will always be valid, but in the sense that it is capable of forcing you to suspend consciousness of time altogether."[16] Crawdaddy! magazine was also enthusiastic in its praise of the album, with Sandy Pearlman describing it as "enchantingly beautiful".[16] Pete Johnson, in his review for the Los Angeles Times, summed up the album as "11 good songs spiked with electronic music, strings, brass, natural and supernatural voices, and the familiar thick texture of McGuinn's guitar playing".[16]

In a contemporary review published in Esquire, music critic Robert Christgau described The Notorious Byrd Brothers as "simply the best album the Byrds have ever recorded".[53] Christgau grouped it with contemporary releases by Love (Forever Changes) and The Beach Boys (Wild Honey), remarking: "[i]t's hard to believe that so much good can come out of one place [i.e. Los Angeles]."[53] In the UK, Record Mirror gave the album a rare five-star rating, commenting "Hard though it was for the Byrds to follow up their near-perfect Younger Than Yesterday album, they've done it with this fantastic disc."[54] Melody Maker was also complimentary about the album, describing it as "A beautiful selection, representing US pop at its finest."[54] Beat Instrumental concluded their review by stating "It's true to say that the Byrds are one of the two best groups in the world. Nobody can say any different with the proof of this album."[54]

In 1997, Rolling Stone senior editor David Fricke described the album as the Byrds' "finest hour" and "the work of a great rock & roll band, in every special sense of the word".[5] On his official website, Robert Christgau again commented on the album, declaring that The Notorious Byrd Brothers (along with its follow-up, Sweetheart of the Rodeo) is "[one] of the most convincing arguments for artistic freedom ever to come out of American rock".[55] Parke Puterbaugh, writing for the Rolling Stone website in 1999, remarked on the presence of "burbling Moog synthesizers and purring steel guitars" on the album, which he ultimately described as "a brilliant window onto an unforgettable place and time".[52]

Legacy

[edit]Over the years, The Notorious Byrd Brothers has gained in reputation and is often considered the group's best work, while the contentious incidents surrounding its making have been largely forgotten.[5][6][16] The album managed to capture the band at the height of their creative powers, as they pushed ahead lyrically, musically and technically into new sonic territory.[3] Band biographer Johnny Rogan has written that the Byrds' greatest accomplishment on the album was in creating a seamless mood piece from a variety of different sources, bound together by innovative studio experimentation.[3] Although the album is widely regarded as the band's most experimental, its running time of a little under 29 minutes also makes it their briefest.

The album was voted the fourth-best album ever in a 1971 ZigZag magazine readers' poll and the 1977 edition of the Critic's Choice: Top 200 Albums book ranked it at number 154 in a list of the "Greatest Rock Albums of All-Time".[56][57] A subsequent edition of the book, published in 1988, ranked the album at number 75.[57] The album was included in Robert Christgau's "Basic Record Library" of 1950s and 1960s recordings, published in Christgau's Record Guide: Rock Albums of the Seventies (1981).[58] In 1995, Mojo magazine placed the album at number 36 in their list of "The 100 Greatest Albums Ever Made".[59] In 2003, the album was ranked at number 171 on Rolling Stone magazine's list of "The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time",[60] maintaining the rating in a 2012 revised list.[61] It also ranked number 32 on the NME's list of the "100 Best Albums".[62] In 2004, Q magazine included the album in its list of "The Music that Changed the World".[63] It was voted number 158 in the third edition of Colin Larkin's All Time Top 1000 Albums (2000).[64]

The Notorious Byrd Brothers was remastered at 20-bit resolution as part of the Columbia/Legacy Byrds series.[65] It was reissued in an expanded form on March 25, 1997, with six bonus tracks, including Crosby's controversial ballad "Triad", the Indian-influenced "Moog Raga", and an instrumental backing track for the outtake "Bound to Fall".[28] The final track on the CD extends to include a hidden track featuring a radio advertisement by producer Gary Usher for the album, as well as a recording of an in-studio altercation between the band members.[66]

Following the release of the album, the Byrds' recording of "Wasn't Born to Follow" was used in the 1969 film Easy Rider and included on the accompanying Easy Rider soundtrack album.[67][68] In addition, the song "Change Is Now" has been covered by the progressive bluegrass band The Dixie Bee-Liners, on the tribute album Timeless Flyte: A Tribute to The Byrds — Full Circle, and by rock band Giant Sand, on Time Between – A Tribute to The Byrds.[69][70] Ric Menck, best known for being a member of the band Velvet Crush, has written a book about the album for Continuum Publishing's 33⅓ series.[71]

Track listing

[edit]| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Artificial Energy" | Roger McGuinn, Chris Hillman, Michael Clarke | 2:18 |

| 2. | "Goin' Back" | Carole King, Gerry Goffin | 3:26 |

| 3. | "Natural Harmony" | Chris Hillman | 2:11 |

| 4. | "Draft Morning" | David Crosby, Chris Hillman, Roger McGuinn | 2:42 |

| 5. | "Wasn't Born to Follow" | Carole King, Gerry Goffin | 2:04 |

| 6. | "Get to You" | Roger McGuinn, Chris Hillman (possibly mis-credited and actually written by Gene Clark and Roger McGuinn[12]) | 2:39 |

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Change Is Now" | Chris Hillman, Roger McGuinn | 3:21 |

| 2. | "Old John Robertson" | Chris Hillman, Roger McGuinn | 1:49 |

| 3. | "Tribal Gathering" | David Crosby, Chris Hillman | 2:03 |

| 4. | "Dolphin's Smile" | David Crosby, Chris Hillman, Roger McGuinn | 2:00 |

| 5. | "Space Odyssey" | Roger McGuinn, Robert J. Hippard | 3:52 |

| Total length: | 28:28 | ||

- Sides one and two were combined as tracks 1–11 on CD reissues.

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 12. | "Moog Raga" (instrumental) | Roger McGuinn | 3:24 |

| 13. | "Bound to Fall" (instrumental) | Mike Brewer, Tom Mastin | 2:08 |

| 14. | "Triad" | David Crosby | 3:29 |

| 15. | "Goin' Back" (alternate - version one) | Carole King, Gerry Goffin | 3:55 |

| 16. | "Draft Morning" (alternate ending) | David Crosby, Chris Hillman, Roger McGuinn | 2:55 |

| 17. | "Universal Mind Decoder" (instrumental; song ends at 3:32; 4:32 begins radio advert which ends at 5:41; 6:42 begins "Dolphin's Smile" [in-studio argument]) | Chris Hillman, Roger McGuinn | 13:45 |

Single release

[edit]- "Goin' Back" b/w "Change Is Now" (Columbia 44362) October 20, 1967 (Billboard chart number 89)

Personnel

[edit]Adapted from So You Want to Be a Rock 'n' Roll Star: The Byrds Day-By-Day (1965–1973), The Notorious Byrd Brothers (33⅓ series), Byrds: Requiem for the Timeless, Volume 1, and the compact disc liner notes.[7][19][28][37][72]

- Roger McGuinn – vocals, lead guitar, Moog synthesizer

- David Crosby – vocals, rhythm guitar on "Change is Now", "Tribal Gathering", "Dolphin's Smile", "Triad", and "Goin' Back" (alternate); rhythm guitar on "Draft Morning", "Bound to Fall" and "Universal Mind Decoder"; vocals, electric bass on "Old John Robertson"

- Chris Hillman – vocals; electric bass all tracks except "Old John Robertson"; guitar on "Old John Robertson"; mandolin on "Draft Morning"

- Michael Clarke – drums on "Artificial Energy", "Draft Morning", "Change Is Now", "Old John Robertson", "Tribal Gathering", and "Universal Mind Decoder"

- Gene Clark – possible backing vocal on "Goin' Back" (master) and "Space Odyssey"

Additional personnel

- James Burton, Clarence White – guitars

- Red Rhodes – pedal steel guitar

- Paul Beaver – piano, Moog synthesizer

- Terry Trotter – piano

- Gary Usher – Moog synthesizer, percussion, backing vocals

- Barry Goldberg – organ

- Dennis McCarthy – celeste

- Jim Gordon – drums on "Goin' Back", "Natural Harmony", "Wasn't Born to Follow", "Dolphin's Smile", "Bound to Fall", and "Triad"

- Hal Blaine – drums on "Get to You" and "Flight 713" (the latter song is only found on the Never Before compilation)

- Curt Boettcher – backing vocals

- William Armstrong, Victor Sazer, Carl West – violins

- Paul Bergstrom, Lester Harris, Raymond Kelley, Jacqueline Lustgarten – cellos

- Alfred McKibbon – double bass (bowed)

- Ann Stockton – harp

- Richard Hyde – trombone

- Roy Caton, Virgil Fums, Gary Weber — brass

- Jay Migliori – saxophone

- Dennis Faust – percussion

- Firesign Theatre – sound effects on "Draft Morning"

- unknown musicians – trumpet on "Draft Morning"; string quartet and additional fiddle on "Old John Robertson"

Release history

[edit]| Date | Label | Format | Country | Catalog | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| January 15, 1968 | Columbia | LP | US | CL 2775 | Original mono release. |

| CS 9575 | Original stereo release. | ||||

| April 12, 1968 | CBS | LP | UK | 63169 | Original mono release. |

| S 63169 | Original stereo release. | ||||

| 1973 | Embassy | LP | UK | EMB 31202 | Stereo reissue with the subtitle Space Odyssey. |

| 1976 | CBS | LP | UK | S 22040 | Double album stereo reissue with Sweetheart of the Rodeo. |

| 1987 | Edsel | LP | UK | ED 262 | |

| 1987 | Edsel | CD | UK | EDCD 262 | Original CD release. |

| 1990 | Columbia | CD | US | CK 9575 | Original US CD release. |

| March 25, 1997 | Columbia/Legacy | CD | US | CK 65151 | Reissue containing six bonus tracks and the remastered stereo album. |

| UK | COL 4867512 | ||||

| 1999 | Simply Vinyl | LP | UK | SVLP 0006 | Reissue of the remastered stereo album. |

| 2003 | Sony | CD | Japan | MHCP-70 | Reissue containing six bonus tracks and the remastered album in a replica LP sleeve. |

| 2006 | Sundazed | LP | US | LP 5201 | Reissue of the original mono release. |

| 2006 | Columbia/Mobile Fidelity Sound Lab | SACD (Hybrid) | US | UDSACD 2015 | Mono album plus stereo bonus tracks. |

Single release

[edit]- "Goin' Back" b/w "Change Is Now" (Columbia 44362) October 20, 1967 (Billboard chart number 89)

Notes

[edit]- ^ The album's precise release date is the subject of debate by biographers and band historians. Most sources, including authors Johnny Rogan, Ric Menck, and Christopher Hjort cite January 15, 1968, but other sources, such as the AllMusic website and the artwork for the Columbia Records 1997 remastered CD, list January 3.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Rogan, Johnny (1998). The Byrds: Timeless Flight Revisited (2nd ed.). Rogan House. pp. 544–546. ISBN 0-9529540-1-X.

- ^ a b c d e f "The Notorious Byrd Brothers review". AllMusic. Retrieved January 10, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Rogan, Johnny. (1998). The Byrds: Timeless Flight Revisited (2nd ed.). Rogan House. pp. 240–247. ISBN 0-9529540-1-X.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "The Notorious Byrd Brothers". ByrdWatcher: A Field Guide to the Byrds of Los Angeles. Archived from the original on May 22, 2010. Retrieved August 22, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Fricke, David. (1997). The Notorious Byrd Brothers (1997 CD liner notes/rear cover).

- ^ a b c d Bob Olsen. "The Byrds – The Notorious Byrd Brothers review". Music Tap. Archived from the original on July 29, 2010. Retrieved February 21, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Hjort, Christopher. (2008). So You Want To Be A Rock 'n' Roll Star: The Byrds Day-By-Day (1965–1973). Jawbone Press. pp. 148–153. ISBN 978-1-906002-15-2.

- ^ a b c Menck, Ric. (2007). The Notorious Byrd Brothers (33⅓ series). Continuum Books. pp. 113–116. ISBN 978-0-8264-1717-6.

- ^ a b c Hjort, Christopher. (2008). So You Want To Be A Rock 'n' Roll Star: The Byrds Day-By-Day (1965–1973). Jawbone Press. p. 117. ISBN 978-1-906002-15-2.

- ^ a b c d e Rogan, Johnny. (1998). The Byrds: Timeless Flight Revisited (2nd ed.). Rogan House. pp. 228–234. ISBN 0-9529540-1-X.

- ^ a b c Rogan, Johnny. (1998). The Byrds: Timeless Flight Revisited (2nd ed.). Rogan House. pp. 237–238. ISBN 0-9529540-1-X.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Einarson, John. (2005). Mr. Tambourine Man: The Life and Legacy of the Byrds' Gene Clark. Backbeat Books. pp. 126–127. ISBN 0-87930-793-5.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Menck, Ric. (2007). The Notorious Byrd Brothers (33⅓ series). Continuum Books. pp. 79–83. ISBN 978-0-8264-1717-6.

- ^ a b Whitburn, Joel. (2002). Top Pop Albums 1955–2001. Hal Leonard Corp. p. 121. ISBN 0-634-03948-2.

- ^ a b Brown, Tony. (2000). The Complete Book of the British Charts. Omnibus Press. p. 130. ISBN 0-7119-7670-8.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Hjort, Christopher. (2008). So You Want To Be A Rock 'n' Roll Star: The Byrds Day-By-Day (1965–1973). Jawbone Press. pp. 157–158. ISBN 978-1-906002-15-2.

- ^ "The Byrds Biography". AllMusic. Retrieved January 10, 2010.

- ^ a b "Michael Clarke Biography". AllMusic. Retrieved January 10, 2010.

- ^ a b c d Hjort, Christopher. (2008). So You Want To Be A Rock 'n' Roll Star: The Byrds Day-By-Day (1965–1973). Jawbone Press. pp. 143–146. ISBN 978-1-906002-15-2.

- ^ Rogan, Johnny. (1998). The Byrds: Timeless Flight Revisited (2nd ed.). Rogan House. pp. 266–267. ISBN 0-9529540-1-X.

- ^ "Crown Of Creation review". AllMusic. Retrieved January 10, 2010.

- ^ "Never Before review". AllMusic. Retrieved August 22, 2009.

- ^ a b "The Notorious Byrd Brothers (Bonus Tracks) review". AllMusic. Retrieved August 22, 2009.

- ^ Selvin, Joel. (1992). Monterey Pop. Chronicle Books. p. 54. ISBN 0-8118-0153-5.

- ^ Menck, Ric. (2007). The Notorious Byrd Brothers (33⅓ series). Continuum Books. pp. 74–75. ISBN 978-0-8264-1717-6.

- ^ Rogan, Johnny. (1998). The Byrds: Timeless Flight Revisited (2nd ed.). Rogan House. p. 223. ISBN 0-9529540-1-X.

- ^ a b Rogan, Johnny. (1998). The Byrds: Timeless Flight Revisited (2nd ed.). Rogan House. pp. 247–248. ISBN 0-9529540-1-X.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Rogan, Johnny. (1997). The Notorious Byrd Brothers (1997 CD liner notes).

- ^ Einarson, John. (2005). Mr. Tambourine Man: The Life and Legacy of The Byrds' Gene Clark. Backbeat Books. pp. 87–88. ISBN 0-87930-793-5.

- ^ Einarson, John. (2005). Mr. Tambourine Man: The Life and Legacy of the Byrds' Gene Clark. Backbeat Books. pp. 112–117. ISBN 0-87930-793-5.

- ^ Larry Wagner (1988). Byrds Gene Clark home video of a great interview (Videotape). KBSG 97: YouTube. Event occurs at 16:30. Archived from the original on 2021-12-13. Retrieved November 16, 2015.

{{cite AV media}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Thomson, Graeme (November 2012). "Change Is Now". Uncut. No. 186. London: IPC Media. p. 33.

- ^ Thomson, Graeme (November 2012). "Change Is Now". Uncut. No. 186. London: IPC Media. p. 35.

- ^ Black, Johnny (September 2002). "Roger McGuinn: Twelve-string Driven Thing". Mojo. Available at Rock's Backpages (subscription required).

- ^ a b c Menck, Ric. (2007). The Notorious Byrd Brothers (33⅓ series). Continuum Books. pp. 85–87. ISBN 978-0-8264-1717-6.

- ^ a b c d Menck, Ric. (2007). The Notorious Byrd Brothers (33⅓ series). Continuum Books. pp. 124–126. ISBN 978-0-8264-1717-6.

- ^ a b Menck, Ric. (2007). The Notorious Byrd Brothers (33⅓ series). Continuum Books. pp. 84–136. ISBN 978-0-8264-1717-6.

- ^ a b c "Goin' Back by The Byrds review". AllMusic. Retrieved January 5, 2010.

- ^ "Artificial Energy lyrics". The Byrds Lyrics Page. Retrieved August 23, 2009.

- ^ Menck, Ric. (2007). The Notorious Byrd Brothers (33⅓ series). Continuum Books. p. 91. ISBN 978-0-8264-1717-6.

- ^ a b c Menck, Ric. (2007). The Notorious Byrd Brothers (33⅓ series). Continuum Books. pp. 103–104. ISBN 978-0-8264-1717-6.

- ^ "Wasn't Born to Follow by The Byrds review". AllMusic. Retrieved January 11, 2010.

- ^ Menck, Ric. (2007). The Notorious Byrd Brothers (33⅓ series). Continuum Books. p. 123. ISBN 978-0-8264-1717-6.

- ^ Menck, Ric. (2007). The Notorious Byrd Brothers (33⅓ series). Continuum Books. p. 93. ISBN 978-0-8264-1717-6.

- ^ a b c d Menck, Ric. (2007). The Notorious Byrd Brothers (33⅓ series). Continuum Books. pp. 97–100. ISBN 978-0-8264-1717-6.

- ^ a b Menck, Ric. (2007). The Notorious Byrd Brothers (33⅓ series). Continuum Books. pp. 117–120. ISBN 978-0-8264-1717-6.

- ^ Hjort, Christopher (2008). So You Want To Be A Rock 'n' Roll Star: The Byrds Day-By-Day (1965-1973). Jawbone Press. p. 127. ISBN 978-1-906002-15-2.

- ^ "Space Odyssey lyrics". The Byrds Lyrics Page. Retrieved August 22, 2009.

- ^ "2001: A Space Odyssey". The Worlds of David Darling: Encyclopedia of Science. Retrieved August 22, 2009.

- ^ Larkin, Colin (2007). Encyclopedia of Popular Music (5th ed.). Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0857125958.

- ^ Gordon, Jeremy. "The Byrds: The Notorious Byrd Brothers Album Review". Pitchfork. Retrieved April 23, 2023.

- ^ a b Puterbaugh, Parke. "The Notorious Byrd Brothers review". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on February 2, 2013. Retrieved November 7, 2010.

- ^ a b "Robert Christgau: June 1968 column". Robert Christgau: Dean of American Rock Critics. Retrieved August 22, 2009.

- ^ a b c Hjort, Christopher. (2008). So You Want To Be A Rock 'n' Roll Star: The Byrds Day-By-Day (1965–1973). Jawbone Press. pp. 167–168. ISBN 978-1-906002-15-2.

- ^ "The Byrds: Consumer Guide Reviews". Robert Christgau: Dean of American Rock Critics. Retrieved August 22, 2009.

- ^ "1971 Reader's Poll: Best Album Ever", ZigZag, London, December 1971

- ^ a b "The World Critics Lists – 1977 & 1988". Rocklist.net. Retrieved March 29, 2010.

- ^ Christgau, Robert (1981). "A Basic Record Library: The Fifties and Sixties". Christgau's Record Guide: Rock Albums of the Seventies. Ticknor & Fields. ISBN 0899190251. Retrieved March 16, 2019 – via robertchristgau.com.

- ^ "Mojo: The 100 Greatest Albums Ever Made". Rocklist.net. Retrieved January 12, 2010.

- ^ "RS 500 Albums: #171 – The Notorious Byrd Brothers". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on November 9, 2007. Retrieved August 22, 2009.

- ^ "500 Greatest Albums of All Time Rolling Stone's definitive list of the 500 greatest albums of all time". Rolling Stone. 2012. Retrieved September 18, 2019.

- ^ "NME's 100 Best Albums – 2003". Rocklist.net. Retrieved January 12, 2010.

- ^ "The Music that Changed the World". Rocklist.net. Retrieved January 12, 2010.

- ^ Colin Larkin, ed. (2000). All Time Top 1000 Albums (3rd ed.). Virgin Books. p. 90. ISBN 0-7535-0493-6.

- ^ Rogan, Johnny. (1998). The Byrds: Timeless Flight Revisited (2nd ed.). Rogan House. pp. 665–666. ISBN 0-9529540-1-X.

- ^ Rogan, Johnny. (1998). The Byrds: Timeless Flight Revisited (2nd ed.). Rogan House. p. 470. ISBN 0-9529540-1-X.

- ^ "Easy Rider Soundtrack". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved August 22, 2009.

- ^ "Easy Rider Soundtrack review". AllMusic. Retrieved February 21, 2010.

- ^ "Timeless Flyte: A Tribute to The Byrds". AllMusic. Retrieved October 23, 2009.

- ^ "Time Between – A Tribute to The Byrds review". AllMusic. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ^ "The Notorious Byrd Brothers by Ric Menck". Continuum Books. Archived from the original on July 17, 2011. Retrieved August 22, 2009.

- ^ Rogan, Johnny (2011). Byrds: Requiem for the Timeless, Volume 1. Rogan House. pp. 1023–1025. ISBN 978-0-95295-408-8.

Bibliography

[edit]- Rogan, Johnny, The Byrds: Timeless Flight Revisited, Rogan House, 1998, ISBN 0-9529540-1-X

- Menck, Ric, The Notorious Byrd Brothers (33⅓ series), Continuum Books, 2007, ISBN 0-8264-1717-5.

- Hjort, Christopher, So You Want To Be A Rock 'n' Roll Star: The Byrds Day-By-Day (1965–1973), Jawbone Press, 2008, ISBN 1-906002-15-0.

- Einarson, John, Mr. Tambourine Man: The Life and Legacy of the Byrds' Gene Clark, Backbeat Books, ISBN 0-87930-793-5.

External links

[edit]- Snopes article about the significance of the horse on the album cover